|

Crime and Immigrant Youth by Tony Waters Department of Sociology and Social Work California State University, Chico (Sage, 1998; 224 pages; $48 hard cover, $21.95 paperback) |

| NOTE: Ethel Dunn reports that most of Water's data came from Pauline Young's work in the 1920's among Pryguny living in the LA "Flats". |

Crime and Immigrant Youth explores the causes of youthful crime in immigrant populations. Using data from 100 years of United States immigration records, particularly from California, Waters examines immigrant groups such as Mexicans and Spiritual Christians from Russia in the early twentieth century and Laotians, Koreans, and Mexicans in the late twentieth century. He discusses the evolution of migrant families and reveals where crime does and does not occur. Numerous case examples show how misunderstandings between immigrant parents and their children often provide conditions for a predictable outbreak of crime. Waters theorizes that as long as this country has a demand for cheap immigrant labor, "second generation" problems of youthful crime and gangs in immigrant communities will persist.

Adapted from: Bookmarks, Chico Statements, |

|

Reviews The author, Tony Waters, May 22, 1999 (From Amazon.com)

Why do gangs sometimes emerge in immigrant groups? |

| This book started as my Ph.D. dissertation. But the publisher assures me that it is "interesting and accessible;" I hope you will also agree.

My book asks a simple question: why do some immigrant groups have waves of immigrant crime, and others do not? More to the point, why do many immigrant groups have lots of immigrant crime at one time, and very little at others? A good example is with immigrants from Mexico. In the 1910s and 1920s, large numbers migrated to Los Angeles where they quickly developed a reputation for being�law abiding. At the same time, the Los Angeles police were aggressively pursuing gangs of Russian youth who had developed a reputation for fighting and stealing. This pattern is repeated today. For example, poor Vietnamese immigrant families have a reputation for producing both valedictorians and some of the West coast's most notorious gang-bangers. What gives? You can't have it both ways. Or can you? Is there something about migration itself which makes such groups different than more settled groups? The argument of my book is that migration is viewed as a process, waves of youthful crime will emerge in poor immigrant communities. These waves have a beginning as children socialized in the United States come of age, and begin to form particularly strong peer sub-cultures. Some (but not all) of these sub-groups turn into gangs. Notably, they do not have a root in the culture brought from the home country, experiences in war, or other events which occurred before migration. Rather they have their roots in the process of migration itself. The book notes that this process is a particular problem in immigrant groups having having high birth rates. But it is not so strong in immigrant groups which have few children. These arguments are developed by using stories from people who have been involved with outbreaks of youthful crime in Laotian, Hmong, Mexican, and Spiritual Christians from Russia Molokan Russian communities. The conclusion of Crime and Immigrant Youth focuses on the policy implications of this study. Notably, it concludes that as long as the United States has a persistent demand for cheap immigrant labor, the "second generation" issue of gang activity will persist. I hope that the book will be of interest to students of the juvenile justice system, law enforcement, criminology, school counselors, and other working with immigrant youth. Tony Waters < email: twaters@csuchico.edu > |

|

|

From: |

A.J. Conovaloff To: twaters@csuchico.edu Cc: Dunn, Ethel Sent: 7/23/99 4:51 PM Subject: From a Prygun Molokan I created the Molokan Home Page to correct dis-information about Update: 2019 March 29 � Before 2011, the term Molokan broadly I haven't yet seen your thesis, and now find available in paperback. So Can you get discounted copies of your book for Molokans? Also, I'd Did you interview any living Molokans in your work? I knew several, and One story I remember (the teller lives in LA) occurred during a Molokan I find your analysis useful in helping the American Molokans put their I'm also interested in seeing your references. |

|

Subject: |

RE: From a Molokan Mon, 26 Jul 1999 22:57:37 -0700 "Waters, Tony" <TWATERS@csuchico.edu> "'A.J. Conovaloff '" <conovaloff@maricopa.edu> Dear A.J. Conovaloff Sincerely, Tony Waters |

|

Subject: |

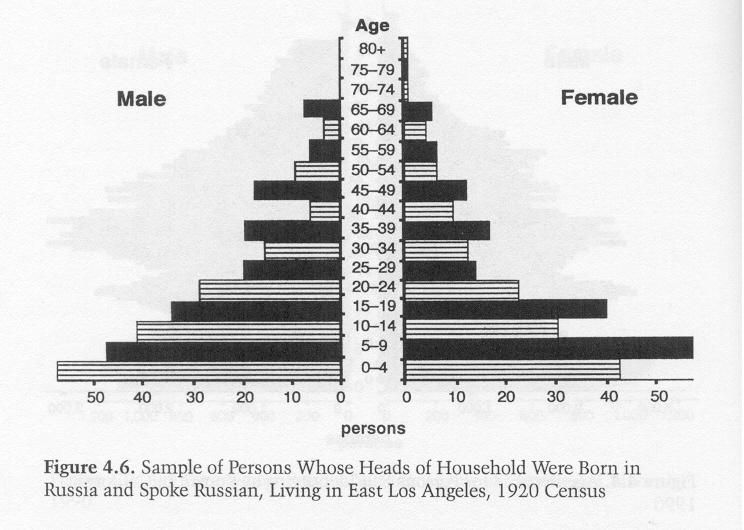

Re: From a Molokan Tue, 27 Jul 1999 09:47:28 -0700 "A.J. Conovaloff" Sure. I'll ask around. You probably missed: "East Los Angeles : history of a barrio" by Ricardo Romo, 1983, (now at Univ Texas, Austin) who somehow missed Young's >What I found interesting about the And they moved from rural villages to a big metropolis. The Doukhobors who were neighbors to Molokans in the Caucasus and moved to Canada just before the Molokans came to America, were settled in the Saskatchewan prairies and had no youth gangs. During immigration, Molokans leaders were split on following the Doukhobors or California. California offered jobs, so they "chased the dollar", not the spirit, as one elder told me. > In the book version, there are also references to the Dunn's Hardwick saw my presentation on Molokan migrations patterns given at the West Coast Geographers Conference about 1980, when I was a business grad student at CSU Fresno. The anthropology dept had just gotten a grant to document the SJ Valley ethnic groups and encouraged me to help with the Molokans and that presentation. I either spoke or wrote to her once, though she kept in touch with Ethel. I wanted to review her work before she published, as I do all researchers. Many American Molokans hate the outside researchers who are making money on their religion, but when offered to proofread manuscripts they feel like they have some control on what is said about them. We have a broad spectrum of fears among our people. Anyway, she continued to publish about Molokans with very little personal contact with us, and hasn't returned any e-mail for over a year. I finally found a copy of her 1980's publication and have a few things to post about it. (One of many projects.) > I sampled from South Pecan, South Gless, and South Clarence Streets They were declassified in 1990 or 1995 (70-75 years later). I did spend 2 days at the Mormon Temple in Santa Monica to realize I needed a few weeks. There was also an early phone book that listed occupations. The UMCA has a copy. The most valuable document on the Flats are the insurance maps archived at CSU Northridge, Geography Dept--each house, out-house, stove pipe is shown, all drawn, most Molokan churches are labeled. I tried getting elders to sketch who lived where in the Flats, but by using original documents, their memories are helped. Interesting, in the 1920 census, was that P.M. Shubin (the leader in front of Young's book) had 20+ people "living" at his house, or using his address. >In 1920, there was a large number of young people coming of age. Did you note the impact of the UMCA's cutting arrests by 50% in 1926. Someday I'll graph that data from Young to really illustrate the impact of forming a youth organization, giving the kids an alternative place to go at night. Note that about a dozen young couples feared melting into America and built something not know in Russia--a youth organization--to compete with the Andy Conovaloff |

| Subject: Date: From: |

Sokolov and Hardwick references Tue, 27 Jul 1999 12:17:09 -0700 "Waters, Tony" <TWATERS@csuchico.edu> The reference for Sokolov is as follows: Sokolov L. (1918) [Lillian Sokoloff] She was a teacher in a Molokan school, as I recall. She was a Russian, but not a Molokan. She very much liked the Molokans in L.A. and described the students as being particularly hard-working and diligent (different than Young). As I recall, she also had some details about World War I era draft resistance, when a number of young Molokan men were sent to prison in Arizona. The monograph is somewhat hard to get; I would suggest that you try inter-library loan. I had to go to the California State Library in Sacramento to get a copy. The most recent reference for Hardwick is a book "Russian Refuge:: Religion, migration, and settlement on the North Pacific Rim." Chicago: University of Chicago Press. It is primarily about Orthodox churches in Alaska and California, I recall. There are thorough sections about both Molokans and Dukhobours. Tony Waters |

|

REVIEW by Andy Conovaloff (in-progress)

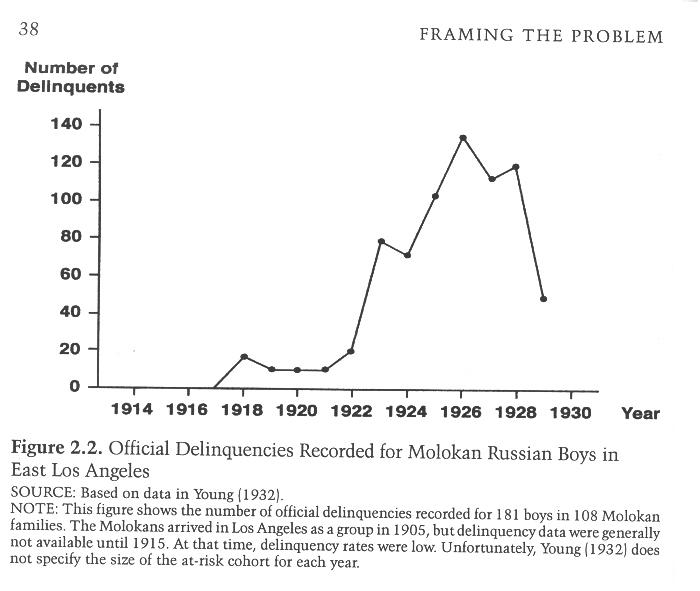

Waters bases his analysis of Molokan gangs on Pauline Young's records from the 1920s and 30s, and some original sampling of the 1920 census records now available for the Flat's area. Though he had not interviewed any Molokan who was a gang member, we can learn a lot from his research. Most important is his conclusion that when immigrant rural families with lots of kids and strong religious and family traditions move to a big city, gang membership and crime is a natural result that, perhaps, cannot be avoided even with intense intervention. (More on his finding later, when I read everything.) Years ago, when I studied The Pilgrims of Russian-Town, I saw a table of the number of juvenile delinquencies recorded for Molokan boys by the Hollenbeck police station. Notable to me was the 50% drop in delinquencies as soon as the UMCA was started in 1926--from about 140 to 60. (See graph on left.) |

|

I had wanted to plot the graph to show the effect the UMCA had on the Molokan ghetto. Tony published the graph first, but he missed the impact of the UMCA and a major reason why so many young families stuck their necks out, donated their money, and disregarded the strong resistance of the elders and the Maksimisti/Chuloks at the time to incorporate a new institution contrary to Molokan tradition--a youth center.

|