A Russian Farmers’

Village

By Marshall R. Bowen,

University of Mary Washington, Fredericksburg, Virginia. |

|

| (Fig.

1) A year ago, at the meeting of this Association in

San Luis

Obispo, I

reported on a long-extinct farmers' village established by

Russian

Spiritual Christians

Molokans

near Park Valley, in northwestern Utah. (Fig. 2) [See: Russian

Colonists in the Utah Desert: Spiritual

Chrisitan Molokan

Community in Utah — 1914

to 1918]

In that

presentation, I described the village's form

and function, (Fig. 3)

explained that it

did not succeed because of

drought induced crop failures, and

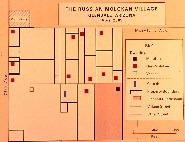

provided a glimpse of its

present-day landscape, including (Fig.

4)

foundations and (Fig. 5) grave

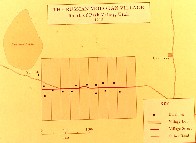

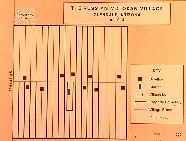

markers. (Fig. 6) Today, I would like to continue my story of traditional Spiritual Christian Molokan villages in the American West, and call your attention to a site in Glendale, about ten miles from Phoenix. (Fig. 7) Modern Glendale is Arizona's fourth largest city — as you can see from this sign — and today it is primarily a succession of subdivisions and shopping malls. (Fig. 8) But Glendale also has a strong rural heritage, as is suggested by this picture, with irrigated fields cultivated by a wide variety of ethnic groups, including the Molokans. (Fig. 9) This paper reviews the movement of these people from Russia to California and then to Arizona, describes the Glendale village and the changes that it has undergone through the years, and illustrates what the site is like today, nearly a hundred years after the first Spiritual Christian Molokan colonists arrived in Glendale. [The legal name of the incorporated congregation was incorrectly filed as: "The Church of Spiritual Molokans of Arizona, Inc." (aka: Jumpers, or Pryguny in Russian). For simplicity Dr. Bowen uses the term Molokan, though most references are about Prygun and Dukh-i-zhiznik families of different faiths. This village was called "the colony" — Russian: koloniia, колония. Many of it's members called their congregation Darichatkskii, from a village in Kars Oblast, Russia.] (Fig. 10) Molokans are one of several groups of fundamentalist dissenters who broke away from the Russian Orthodox church in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Their belief system is complex, but at its core is nonviolence, rejection of the worship of icons, refusal to follow the leadership of priests, the importance of Prygun prophesies, and certain dietary restrictions. Their name is derived from the Russian word for milk drinkers because they refused to abstain from consuming dairy products during Lent and other times of fasting. (Fig. 11) Because of their non-conformist views and opposition to military service, thousands of Spiritual Christians Molokans living in central Russia were sent into exile, some of it forced but much of it of a more voluntary nature. These movements took them first to the south Ukraine and Volga River region and then to Transcaucasia. (Fig. 12) Some men were merchants and artisans, but the majority were peasant farmers living with their families in traditional street villages, such as this one, that closely resembled the communities that they had left behind. (Fig. 13) Spiritual Christians Molokans living in Transcaucasia enjoyed considerable prosperity and religious freedom, but in the early 1900s, fearing that their young men would be forced into military service, hundreds of families living near the Turkish border fled to the United States, with almost all of them ending up in California. (Fig. 14) Some established homes in San Francisco, but by far the largest number made their way to Los Angeles, where they gathered on the "Flats" east of the city's Central Business District in an area known as Russian Town. (Fig. 15) This is a picture of one of the streets in Russian Town. Here, men found jobs in lumber yards and factories, and in many cases they were able to purchase modest houses shortly after their arrival. (Fig. 16) Despite these outward signs of success, many Spiritual Christians Molokans were dissatisfied with city life. Most men had been farmers for years, and were anxious to return to the land, where they could resume familiar lifestyles. Parents were concerned that their children were being exposed to undesirable American values, and believed that the best way to preserve Spiritual Christian Molokan culture was to relocate to rural areas where they could live traditional lives, unaffected by outside influences. (Fig. 17) The first steps in this direction took them to Mexico, where they established a substantial colony in the Guadalupe Valley of Baja California, and three smaller settlements near Ensenada. You can see these on the map just south of the United States-Mexico border. Searches for land in the United States initially met with failure, and it was not until 1911, when families living in Los Angeles moved to Arizona, that another traditional Spiritual Christian Molokan village, resembling those in Russia and in Mexico, came into existence. (Fig. 18) Acquisition of land in Arizona was carried out under the direction of Michael P. Pivovaroff, — shown here in this picture — a presiding elder of a small congregation in Russian Town who had been unable to find suitable land for his people in California. When contacted by a real estate firm acting on behalf of a Glendale sugar company, which needed farmers to grow beets for its plant, Pivovaroff agreed to send a delegation to Arizona to investigate. (Fig. 19) The men visited Glendale in the summer of 1911, — and this is a picture from that visit — and they found a piece of undeveloped but irrigable land, to be watered by the new Salt River Project, southwest of town. Although Spiritual Christians Molokans had no experience with irrigation, the delegates agreed that this was what they were seeking, and contracted to purchase 400 acres for $125 an acre, with just a minimal down payment. (Fig. 20) The initial party of settlers, numbering about 35 families, arrived in Arizona on the first day of September, 1911. Upon reaching the land that their representatives had purchased, many were dismayed to find that the property was still covered by cactus and other desert plants, and infested with snakes, tarantulas, and scorpions. This is a more modern day picture, but it gives you some sort of a sense as to what the environment that those first Molokan settlers encountered. But with the assistance of a sugar company official who convinced local merchants to extend them credit, the newcomers were able to purchase tents, cots, and tools needed to clear the land, and began hauling water from the town pump in Glendale, some two miles distant. (Fig. 21) The next step was to allocate home sites, a process described in these words by the son of one colonist, this picture is not of that particular individual, but the one who did write this said, and I quote: “The elders, pursuing the

customs

of the native villages, laid out the

settlement in the centre of their newly purchased land.

Some 40 acres

were set aside. In the centre was a street and lots were

set aside for

the use of each family as a homesite. Thus there were 40

plots in this

new village and in the centre one plot was reserved for

their [church].

The remaining 39 lots were available for settlement by

each family, and

as there were only 30 families they had nine lots left

over for any new

members. All plots were numbered and each family drew

out the number

that would be their homesite."

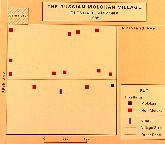

(Fig. 22) The families lived in tents for several months, when most energy was directed toward clearing and plowing the land. In the spring of 1912 the men started building houses, pooling their efforts late each afternoon after working in the fields, to erect one structure at a time under the guidance of this man, an experienced carpenter, (Fig. 23) Each building — as you can see from this picture — was made of lumber, contained only two rooms when first built, and like Russian peasant Molokans farmhouses in Guadalupe Valley and elsewhere, was aligned with the gable end facing the street so that houses sat length-wise on the narrow lots. During this formative period several families, discouraged by the climate and harsh living conditions, returned to Los Angeles, reducing the number of village lot holders to twenty. (Fig. 24) By 1913 the village contained ten occupied dwellings, some situated on single lots that were sixty-six feet wide and about 660 feet deep, while others occupied larger consolidated properties that some of the more prominent members had put together by acquiring unallocated lots and those vacated by people who had gone back to California (Fig. 25) This is something you can certainly see on this map, the long narrow lots and sometimes several lots combined into one person's ownership. A modest church building, shown here, stood near the center of the village on a parcel that had been carved from two adjoining lots, a slight reconfiguration of the original plan. (Fig. 26) One or two dwellings — of the ones shown in this map here — housed single families, but most were shared by several families, usually on a kinship basis. A small number of grave markers stood just beyond the village's northwestern boundary, — you can see that in the upper left-hand part of this map — on land owned by a cooperative non-Russian neighbor that would not be purchased by the Spiritual Christians Molokans until funds were raised in 1921. (Fig. 27) With the exception of gardens planted near the houses, all cropland lay beyond the village. The first settlers had purchased just 400 acres, including the village site, with individual parcels ranging from fewer than ten acres to as many as forty, as you can see on this map here. A half-dozen years later, things had changed and they owned a great deal more land. As a matter of fact by now the village lot holders had nearly doubled their ownership of outlying land to 764 acres, all but a tiny fraction located within a mile of their homes. Several men rented additional land from non-Russians Molokans, some of it as much as eight miles away. (Fig. 28) As planned, the Molokans began by planting sugar beets, but crop failures and closure of the sugar factory in 1913 forced them to turn to other types of farming, particularly dairying, as is illustrated by this particular picture. (Fig. 29) Then, with the beginning of the First World War, cotton prices rose dramatically, and the Spiritual Christians Molokans, like other farmers in central Arizona, switched their attention to this crop, bringing unprecedented prosperity to the community. This picture was taken just a few years ago and is west of Glendale but does illustrate the importance of cotton in the early days as well. (Fig. 30) Despite its promising start, the village did not develop any further, and gradually declined. Some changes were products of personal choices and family tragedies, but others were caused by political and economic forces that lay beyond the villagers' control. Three original lot holders — including the man pictured in this picture here — departed for periods of one to five years to live in Spiritual Christian Molokan colonies in Mexico and eastern Washington, and while each came back to Glendale before the end of 1918, none resumed living in the village. (Fig. 31) Others moved directly to homes built on their outlying properties, in part because of overcrowding in the small village houses — as you can imagine from looking at this picture of these two large families — and partly because they wanted to be closer to the fields where they did most of their farming. (Fig. 32) Two additional men left the village after being imprisoned for their refusal to register for the draft during the First World War. One, and this is not the person himself, was sent home after he signed the registration papers, but during his absence his cotton crop had gone unpicked and death had claimed both his wife and infant son. Disheartened, he moved back to Los Angeles, remarried, and tried to make a fresh start. He actually did come back to Glendale later but it was several years later. (Fig. 33) Another, and again this is not the specific person, who was adamant in his refusal to register, was sent to federal prison, where he endured severe corporal punishment and months of solitary confinement. When he returned home in January, 1919, he seemed ready to resume the life he had know before his ordeal. But a short time later he too departed, because like many of the most zealous Maksimisty and Pryguny Molokans, he was convinced by prophesy that the time was approaching for another flight to a new refuge, and went to Los Angeles to prepare for the journey. (Fig. 34) By 1920 only five of the original lot holders were still living in the village, as you can see from this map of the houses in the villages in 1920. One former resident died, eight were residing elsewhere in Glendale, while several others now made their homes in Los Angeles. Of the five vacated dwellings, four had become the homes of new owners. Three of these were adult sons of an original lot holder, who had moved out of their parents' house. The fourth was a relative, through birth or by marriage, of five original lot holders, and he had been living nearby for at least a half-dozen years. The fifth vacated dwelling was not occupied, and may have already been demolished. (Fig. 35) Additional changes occurred after the cotton market collapsed in late 1920, driving eighty percent of Glendale's Molokan farmers into bankruptcy and forcing several villagers to return to California. And this is a sort of a joke-type picture suggesting the route that some of them had to follow back to California. (Fig. 36) The community was further weakened by the loss of a respected leader, shown in the middle in this picture, who was killed in a farming accident in 1927, and by the departure of his widow and most of their children to Los Angeles a short time later. (Fig. 37) As these families moved away, non-Russians Molokans — represented by this picture right here — purchased or rented their properties, creating a very different social environment. By 1930 the village contained only two Russian Molokan households and five dwellings occupied by non-Russians. All of the new families had roots in Kansas or Oklahoma. Four were engaged in farming, while the fifth was made up of two young school teachers, and their daughter. (Fig. 37-A) Of the Russian Molokan households, one consisted of a farmer, his wife and children, while the other was that of the farmer's elderly parents, who lived next door. (Fig. 38) To make the remainder of this story very short and overly simplified, transformation of the village continued through the 1930s and beyond. Some original houses were torn down and replaced by new structures, — such as this one shown in this picture — while others were allowed to fall into disrepair. (Fig. 39) By mid-century only seven families lived in the village, and just two were Russian Molokan. The adult members of both Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan households died in the 1950s, and for several years not a single family of this faith made its home here. (Fig. 40) This situation is captured by a map of Glendale's Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan church membership in 1971, which shows that about half of the congregation was living within a mile of the village site where the church and cemetery remained focal points of community life, but that no members lived within the village itself. At this time five non-Russian Molokan families had homes on the village street, another lived within the village boundaries in a house on 75th Avenue, while still another had a home, built in the mid-1960s, that fronted on Maryland Avenue, which now defined the village's northern perimeter. There is some question as to whether there might have been one Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan family still living in the village, but it's not shown on this map which was based on a map drawn by a member of the Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan community back in 1971. (Fig. 41) In the mid-1970s the oldest son of this family, Mike P. Tolmachoff, shown in the far left in this photograph, who by now was in his sixties, moved back into the village, — indeed he had been away. Here he would live for the rest of his fife, but for years he and his wife would be the site's only Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan residents. (Fig. 42) In 1985 their house, built around 1940 to replace the original structure, was one of seven occupied dwellings facing the village street. Their house is shown in the lower right-hand part of this particular map. By now, three houses fronted on 75th Avenue, and three other dwellings were on Maryland Avenue.(Fig. 43) Later, Mike Tolmachoff’s brother Harry also returned to the village, but shortly after the beginning of this century his period of residence, like that of Mike, was cut short by death. (Fig. 44) Today, most early settlers’ outlying fields have become residential subdivisions. And this is one just beyond the eastern edge of the old village boundary. (Fig. 45) In the midst of this, remnants of the past — as you can plainly see here — stand side-by-side with unmistakable evidence of a non-Russian Molokan presence along the village's single street, which is now a dead-end street. (Fig. 46) A few original houses, now greatly modified, — such as this one right here — stand beside the street, but they are outnumbered by modern structures (Fig. 47) such as this one, built six years ago to replace an old Russian Molokan house on the owner's property. (Fig. 48) Some original lots remain intact, and you can certainly see that on this map where some of these lots correspond to the map you saw that related to the 1913 situation. But many others have become fragmented, while others have been consolidated. The largest parcel is now owned by a non-Russian Molokan who is married to the granddaughter of one of the original settlers. This property occupies the southwest, the lower left part of the map as you are looking at it here. Only the church grounds and the cemetery are fully in Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan ownership hands. In April, 2005, two dwellings were vacant, and one of them, an original Russian Molokan house on the north side of the village street, indicated by the square that has not been filled in, was slated for demolition and would be replaced by a modern structure, though it does still stand. A more dramatic change was about to take place on a five-acre parcel in the southeastern part of the village, which had been purchased from Mike Tolmachoff’s heirs by a real estate developer, who intends to get this property rezoned, and will subdivide it, and build fifteen single-family homes. And this property is indicated by a slightly darker color on this map. In the meantime, a relative of Tolmachoff was living in the house on this property, which will be torn down when development begins. This house has since been vacated. It's is now empty, but it hasn't yet been torn down. On Maryland Avenue, what were once the back ends of village lots have become house sites and front yards. (Fig. 49) [Aerial views were not used in presentation.] This is one of the houses on Maryland Avenue. (Fig. 50) The southern end of one of these lots, shown here, is now a back-yard junk area, a complete reversal of what existed when the Molokans lived here. (Fig. 51) If you look closely at this picture, you can also get a since of how narrow those early lots are. I took this picture standing on the village's street. The fence in the foreground indicates one side of the 66-foot wide lot, and the fence over beyond the horse-trailer is the fence on the other side. It's only 66 feet across from one side to the other. Zoning provisions which reflect the site's agricultural origins make it possible for present landowners to have cultivated fields, (Fig. 52) such as this alfalfa field you see here, (Fig. 53) to keep horses, this is in the northwestern part of the village, (Fig. 54) raise some cattle, this is in the front yard of a non-Russian Molokanhouse, (Fig. 55) care for a small flock of sheep, which on this picture are actually grazing on the old Mike Tolmachoff property, and (Fig. 56) let poultry run loose within the old village boundaries. (Fig. 57) Descendants of the original Spiritual Christian settlers who live in the surrounding area ordinarily come to the village only to attend services in the church building, shown here, which replaced the first one in 1950s, and (Fig. 58) to visit the cemetery, shown in this picture, which contains simple wooden markers dating back to earlier times as well as those of more recent vintage. These and other landscape features, (Fig. 59) such as this barn on the former Mike Tolmachoff property, are clear reminders of the heritage of this special place, which has not yet been fully absorbed by suburban sprawl, but is nonetheless losing its identity to the forces of modernization that have become so powerful in metropolitan Phoenix. (Fig. 60) Thank you very much.  I welcome all comments. Presentations are limited to 15 minutes, so this is a very abbreviated summary, and as you can see, some aspects are not mentioned at all and others are just touched upon in a most cursory way, but that's the way it has to be with conference papers. I' m hoping to write a longer comparative essay on the Glendale village and the village in Park Valley, but this lies at some distance in the future. Marshall R. Bowen Distinguished Professor of Geography (Emeritus) Department of Geography University of Mary Washington 1301 College Avenue Fredericksburg, Virginia 22401-5300 E-mail: mbowen@umw.edu. Telephone: (540) 654-1493 ?? Fax: (540) 654-1074 TTY: (540) 654-1104 |

CLICK

on

pictures to ENLARGE Many photos have not yet been scanned for posting.  Fig. 1: Kalpakoff home near Park Valley, Utah, c. 1924.  Fig. 2: Molokan village near Park Valley, Utah, c. 1924.  Fig. 3: View from Russian Knoll of Molokan Village near Park Valley, Utah.  Fig. 4: Foundation of Molokan school near Park Valley, Utah.  Fig. 5: Mary Kalpakoff grave in Molokan Village near Park Valley, Utah.  Fig. 6: Molokan villages in the American West  Fig. 7: "Welcome to Glendale" sign at 75th & Camelback Avenues.  Fig. 8: "Tolmachoff Farms" sign on 75th Ave. south of Camelback, at nearby farm of Jumper descent.  Fig. 9:  Fig. 10:  Fig. 11: Molokan family in Russia  Fig. 12:  Fig. 13:  Fig. 14:  Fig. 15:  Fig. 16:  Fig. 17: Molokan settlements in the American West.  Fig. 18: Mikhail Petrovich Pivovarov (1871-1934) founded the Arizona Molokan-Jumper colony  Fig. 19: Opening of new irrigation gate at Grand Ave. for Molokan settlers, 1911. The elders wear Russian caps and tunic shirts, kosovorotki. Younger imigrants adapted overalls and western hats.  Fig. 20: Example of undeveloped desert land purchased by Russian settlers.  Fig. 21:  Fig. 22:  Fig. 23:  Fig. 24: The Russian Molokan Village, Glendale Arizona. c. 1913. 40 acres.  Fig. 25:  Fig. 26:  Fig. 27: Land Controlled by Molokan Village Lot Holders, Glendale, Arizona. 1916-1917. About 400 acres.  Fig. 28:  Fig. 29: One of a few remaining cotton farms 2 miles west of Molokan Village, on Camelback Ave. at 87th Ave., between a sub-division and recent freeway, showing the new Glendale football stadium and sports- entertainment complex a mile away, to the north on Glendale Ave.  Fig. 30: Molokan couple.  Fig. 31:  Fig. 32:  Fig. 33:  Fig. 34: Residences of Original Molokan Village Lot Holders, Glendale, Arizona. 1920.  Fig. 35:  Fig. 36:  Fig. 37:  Fig. 38:  Fig. 39:  Fig. 40:  Fig. 41: Residences Molokan Church Members, Glendale, Arizona. 1971.  Fig. 42: Mike P. Tolmachoff, far left.  Fig. 43: The Russian Molokan Village, Glendale, Arizona. 1985.  Fig. 44: Former residence of Harry P. Tolmachoff, an original house remodeled and owned by decendants who are no longer members of the church.  Fig. 45: New Camino Estates sub-division east of Molokan Village.  Fig. 46: The beginning of Griffith Ave., the only street in the 40-acre Molokan Village.  Fig. 47: Former Molokan house, stuccoed with additions, 7402 Griffin Ave., across the street from the church. Original gable faces street.  Fig. 48: Becky Johnson's new house, 7339 Griffin Ave., adjacent to the church.  Fig. 49: The Russian Molokan Village, Glendale, Arizona. April 2005. Fig. 49a: Molokan Village aerial view about 2000 feet high from West, 2005. Fig. 49b: Molokan Village aerial view about 2000 feet high from East, 2005.  Fig. 50: Boldengro house, 7317 Maryland Ave., at north-edge of Molokan Village.  Fig. 51: Junk in narrow yard of house on Maryland Ave. at north-edge of Molokan Village.  Fig. 52: Alfalfa field on south-side of Molokan Village seen from 75th Avenue.  Fig. 53: Horse pastured in center of Molokan Village.  Fig. 54: Cow in front yard of non-Molokan house owned by Abornes, who are of Russian-Jewish descent.  Fig. 55: Steve Beatty's sheep grazing across Griffith Ave. on the old Mike Tolmachoff property.  Fig. 56: Turkeys and other poultry graze along Griffith Ave.  Fig. 57: Molokan-Jumper Church, 7402 Griffin Ave., Glendale, Arizona. 2005.  Fig. 58: Molokan Cemetery 2005 showing graves (L to R) of Annie Pete Tolmachoff 1919-91, Harry Pete Tolmachoff 1926-2002, Pete Mike Tolmachoff 1909-94.  Fig. 59: Camino Estates sign with Mike P. Tolmachoff barn in background.  Fig. 60: Home-made sign near end of Griffith Ave. |

Photo CreditsAll maps by Dr. Bowen: Figs. 2, 6, 17, 24, 27, 34, 41, 43, and 49. Data for Figs 6 and 17 from Conovaloff and Hardwick. Data for Figs. 24 and 34 from Veronin, map insert by Conovaloff. Data for Fig. 41, from Popoff maps.All color photos by Dr. Bowen, except for Figs. 29, 49a and 49b which were inserted by Conovaloff. Fig. 19 from Sally Tolmachoff, (late husband: Pete M.). Her father is in this photo which was printed in the Phoenix Gazette in 1911. Figs. 49a and 49b from Google Earth. America's Communal Utopias, by Donald E. Pitzer (1997) Appendix: America's Communal Utopias Founded by 1965 "Molokan Community (1911-?); Glendale, Arizona." Book Utah People in the Nevada Desert: Homestead and Community on a Twentieth-Century Farmers' Frontier, 134 pages. Utah State University Press.1994. Chapter One: The Framework, pages 1-6. In this analysis of 2 communities that migrated from Utah to near Wells, Nevada, from 1900 to 1915, Bowen explains why the Mormons prospered by 1925 compared to their neighbors. Articles, Papers "A Russian Molokan Farmers' Village in Northwestern Utah". Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, Cal-Poly State University, San Luis Obispo, California. September 8-11, 2004 "Russian Colonists in the Utah Desert: Spiritual Christian Molokan Community in Utah — 1914 to 1918." Association for Arid Lands Studies, Western Social Science Association 26th Annual Conference, Las Vegas, Nevada. April 10, 2003 "Turnover of Pioneers and Property in a Marginal Nevada Farming Community", Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, Volume 42, 1980 "Cognitive factors and utilization of the Nebraska Sandhills Potash Lakes", Bulletin of the Illinois Geographic Society, Volume XIV, No. 1, June 1972, page 3 “Trees for a Desert Town,” Virginia Geographer 9 (1974): pages 3-7. Award The H. H. Douglas Distinguished Service Award in 1998 for his many contributions to the Pioneer America Society |

|

Spiritual Christians in Arizona

Molokane, Pryguny and Dukh-i-zhiniki Around the World