3. Origins of the Subbotniki Sect

Many people in the Molokan/Subbotniki communities living in Los Angeles that I have talked to believe that the Subbotniki religion is just a variation of the Molokan faith. Pauline Young in her 1932 book, The Pilgrims of Russian-Town5, based on her PhD thesis including many interviews with Molokan elders living in the Flats, reports that the Subbotniks who settled in Los Angeles share a common heritage with the Molokans:The

Molokan sect. … divided

further; and its most important offshoots are Subbotniki, or

Sabbatarians, or Judaized Russians, who modified Molokan

doctrines

under the supposed influence of Jewish scholars of the

nineteenth

century....

However, other sources claim that the Subbotniki had a separate beginning. The Icon and the Axe6, published in 1966, has been used for years as an authoritative source in Russian history courses in universities across the county. Its author, James H. Billington, writes that the Subbotniki sect had its own unique origin as part of the sectarian movement during the reign of Tsar Alexander I in the 1820’s.

The

idea

of a church unifying Christians and Jews was gaining

grass roots support in the Orel-Voronezh region with the

sudden

appearance of

the sabbatarian (Subbotniki)

sect. They added to the usual rejection

of {Russian} Orthodox forms of worship to the doctrine of the

trinity,

celebration of Saturday as the Sabbath, and the rite of

circumcision. …

It taught that all men could be rabbis and

the coming of the Messiah would be an occult philosopher who

would

unlock the

secrets of the universe.

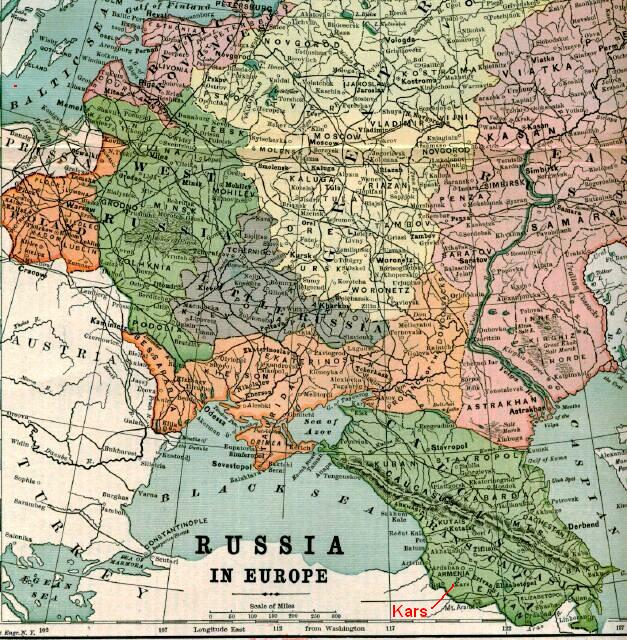

Voronezh province is located next to Tambov province where many sectarian groups including the Molokans originated. Voronezh was once called Woronetz as on the map below which was published in 1898. Also note that this rare map shows the Russian Empire with its Transcaucasia borders extending into eastern Turkey including the Mt.Ararat and the region surrounding the city of Kars. Many Molokans and Subbotniki settled in the Kars area after the Tsar’s army conquered it in 1878. In 1921 the Treaty of Moscow returned this land to Turkey.

Map of

Russia circa

1898 showing borders of Trans-Caucasia extending

west beyond Kars, Turkey

Dubnow1 claims that the Sabbatarian sect first gained the notice of Russian officials in 1817 when they discovered "the ominous spectacle of huge numbers of Christian embracing a doctrine closely akin to Judaism" in the districts of Voronezh, Saratov and Tula" — all of which were not known to have any indigenous Jewish inhabitants. The Orthodox Archbishop of Voronezh reported the following:

The

sect

came into existence about 1796(1)

through

natural Jews. It afterward spread to several settlements in

the

districts of Bobrov and Pavlosk. The essence of the sect,

without being

directly an Old Testament form of Jewish worship, consists of

a few

Jewish ceremonies, such as Sabbath observance and

circumcision, the

arbitrary manner of contracting and dissolving marriages, the

way of

burying the dead, and prayer assemblies. The number of avowed

sectarians amounts to 1,000 souls of both sexes, but the

secret ones

are in all likelihood more numerous.

The Archbishop instituted various measures to deal with the situation including the deportation of a soldier named Anton Rogov who was found to be a “propagandist of the heresy.” Still the movement spread to farmers and merchants in surrounding areas. When confronted, the Sabbatarians responded that they desired to return to the Old Testament and “maintain the faith of their fathers, the Judeans.”

According to Dubnow1, the Committee of Ministers approved the following “draconian project:”

The

chiefs and teachers of the

Judaizing sects are to be impressed into

military service, and those unfit to serve deported to

Siberia. All

Jews are to be expelled from the districts in which the sect

of

Sabbatarians or “Judeans” has made its appearance. Intercourse

{commercial} between the Orthodox inhabitants and the

sectarians is to

be thwarted in every possible manner. Every

outward display of the sect, such as holding of prayer

meetings and the

observance of ceremonies which bear no resemblance to those of

Christians, is to be forbidden. Finally, to make the

sectarians an

object of contempt, instructions are to be given to designate

the

Sabbatarians as Zhydovskaya(2) and to publish

far and wide that they are in reality Zhyds, inasmuch as their

present designation as Sabbatarians, or adherents of the

Mosaic law,

does not give the people a proper idea concerning this sect,

and does

not excite in them that feeling of disgust which must be

produced by

the realization that what is actually aimed at is to turn them

into Zhyds.

Dubnow1 says that these and other policies were sanctioned by Tsar Alexander I in 1825 and that as a result,

Entire

settlements were laid waste,

thousands of sectarians were banished to Siberia and the

Caucasus. Many

of them, unable to endure the persecution, returned to the

Orthodox

faith, but in many cases they did so outwardly, continuing in

secret to

cling to their sectarian tenets.

From the content of Raphael and Jennifer Patai’s discussion of the Subbotniki in their book The Myth of the Jewish Race7 must have used Dubnow’s book1 as a source. However they expand on the cruelty afforded the Subbotniki:

In

1823 the Russian government took

strong measures against the Subbotniki, whose numbers it

estimated at

20,000. Their leaders were conscripted into the army; those

unfit for

army service were exiled to Siberia; the Jews who lived in the

districts infected by the heresy were deported; and all

sectarian

activities, gatherings, customs, and so on were strictly

forbidden. The

sect was called “Jew sect,” so as to make it clear to all and

sundry

that its members were actually converts to Judaism. As a

result of

these measures whole villages were ruined, thousands of

sectarians

banished to Siberia and the Caucasus, and small children taken

away

from their parents to be brought up in Christianity.

The last sentence the above citation is interesting in that the Molokans suffered a similar fate. It may be that the authors are jumping to a more generalized statement about all sectarians at that time.

Further accounts of the emergence and persecution of the Subbotniki are contained in a recent by book by Masha Greenbaum, The Jews of Lithuania8:

….

The emergence of a religious

movement of peasants in Central Russia who called themselves

Subbotniki

(Sabbath observers), and were perceived to have converted to

Judaism.

An indignant Tsar Alexander I subjected the Subbotniki to

terrible

abuse, including deportation to Siberia. Although no Jewish

connections

or influence was involved … no Jewish communities

existed in provinces

where the Subbotniki flourished … officials held the Jews

collectively

responsible [for] Subbotniki religious ideas.

Ms. Greenbaum goes on to report that officials used the Subbotniki phenomena to renege on promises to improve the conditions of Jews living in Russia. The Patais confirm that the Subbotniki experience had an impact on the greater Jewish community in Russia:

The

fear of proselytizing by the

Jews, which produced the reaction to the Subbotniki, also led

to

restrictive laws (1820) prohibiting Jews from having Christian

servants. In 1821 the Jews were expelled from the villages of

White

Russia. By 1827 some 20,000 Jews had been thrust out; many of

these

died of hunger, the cold and diseases.

The Soviet historian A. I. Klibanov in his book History of Religious Sectarianism9, translated into English by Ethel Dunn in 1982, also writes of the Subbotniks as a unique sect and confirms the harsh measures employed against them. He reports that there were between 15,000 to 20,000 Subbotniki living in 28 regions of Russia at the beginning of the nineteenth century:

The

participants in these communities

engaged in petty crafts and trades and the wealthier of them

in money

lending (for example in the Trans-Caucasus).

In 1825 {the government} adopted a special resolution directed toward cutting off the spread of the Subbotnik movement with extremely harsh repressive measures, which, it should be noted had no success. The Subbotnik religious tendency … appeared as a peculiar form of social protest of the peasants directed against the ruling {Orthodox} church.

In 1825 {the government} adopted a special resolution directed toward cutting off the spread of the Subbotnik movement with extremely harsh repressive measures, which, it should be noted had no success. The Subbotnik religious tendency … appeared as a peculiar form of social protest of the peasants directed against the ruling {Orthodox} church.

This situation continued until the reign of Tsar Alexander II. In 1887 the government allowed the Subbotniki to again publicly conduct their own brand of marriage and burial services. An ukase [a government manifesto or decree] issued in 1905 seemed to reverse the plight of the Subbotniki entirely as it abolished discrimination against the sect and directed that they no more be considered as Jews. This ukase and the distinction it made may have saved some Subbotniki living from the Nazi Holocaust — see the section about Subbotniki living in France later in this report.

Are the two versions of the origin of the Subbotniki discussed in the previous paragraphs in this section (Molokan spin-off or unique beginning) contradictory? Not necessarily. Klibanov states that the Tsar’s government was concerned about the spread of the faith. This indicates that there was some degree of proselytizing by early followers of the Subbotniki doctrine. His book also indicates that the sect spread within the Tambov region and eventually expanded to Transcaucasia.

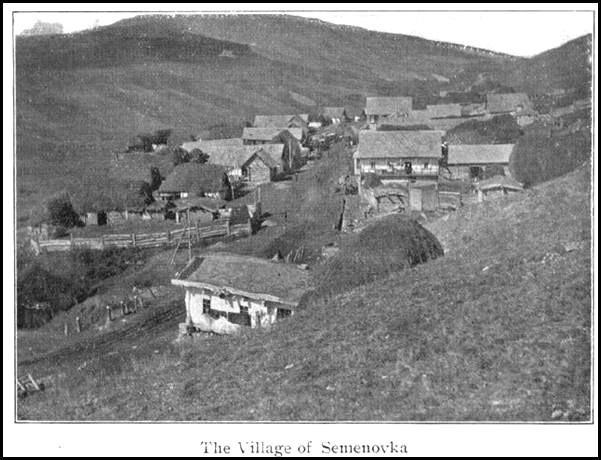

Many Molokans were sent in forced exile to Armenia and Georgia in Transcaucasia during the mid-19th century and later into the Kars region of Russian conquered eastern Turkey. Some Molokan family histories include accounts of Subbotnik evangelists visiting them in the Armenian mountain village of Semenovka in the 1870’s. These evangelists persuaded some family members to adopt the Saturday Sabbath and other Subbotniki practices.

The above picture was taken in 1895; courtesy of National Geographic Magazine, Vol. XII No. 8 August, 1901

This activity led to conflict and turmoil among the villagers. Many households became divided along religious lines. Sons who did not follow in the ways of their father who had converted to the Subbotnik religion were sometimes cut off from the rest of the family and did not receive an inheritance. Some of the family names of those that experienced this schism are Androff, Bogdanoff, Moiseiev, Patapoff, Pivovaroff, Saltikov, Samarin, Shubin, Slivkoff, Tolmasoff and Urkoff(3).

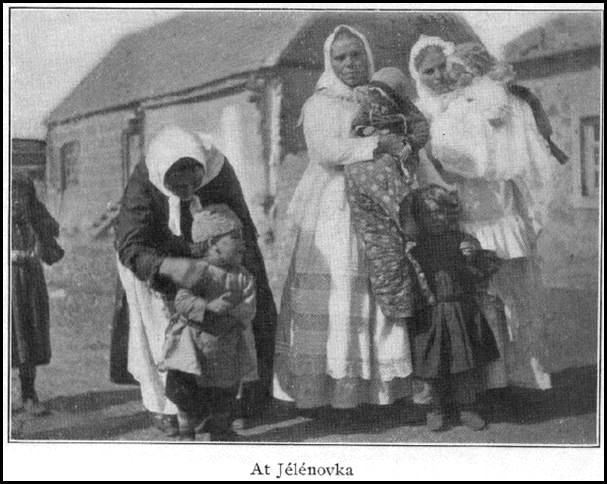

The above picture was taken in 1895; courtesy of National Geographic Magazine, Vol. XII No. 8 August, 1901

Some of these split families co-existed in the same village while other Subbotnik families chose to resettle and congregate in villages with others of similar beliefs. Yelenovka (or Jelenovka), which is called Sevan in today’s Armenia, was one such village that became Subbotnik. Yelenovka is on the shore of Lake Sevan, at the base of the mountain road leading to Semenovka. Some tombstones can still be found today in Semenovka with the dates numbered by the Mosaic calendar. [See Subbotniki in Sevan, Armenia, a segment from the video: "Jews in Armenia: The Hidden Diaspora", with photos and interviews of the congregation in 2001.]

Although living separate religious lives, the two groups shared many of the same hardships and persecution that Russian sectarians experienced during this period. They needed to interact with each other through commerce and service trades in order to survive. Younger family members maintained contacts and intermingled with their former neighbors, cousins and friends. So, it was not unusual that the Transcaucasian Subbotniki left Russia during the same period as the Molokans: 1905-10. However, by the time of the mass migration to America in the first decade of this century, the Subbotniki converts assumed their own identity.

Notes

- In a footnote, Dubnow1 cites subsequent accounts giving the originating year to be 1806.

- An adjective meaning “a Jewish sect” that is derived from Zhyd, the Slavic form of the Latin Judaeus, which has a derogatory connotation in the Russian language.

- Note that the name Aldacushion {Aldakushin} is not listed here, as I have no evidence of the family being Molokan. My grandfather Osip Yegorich Aldakushin married Esther Vassilievna Pivovaroff, the daughter of Vassily Makarich Pivovaroff and Mary Samarin. The name Aldakushin can be found in Russia as late as 1984 when Evgenii Andreivich Aldakushin co-authored a book in Minsk about the Russian resistance during WW II.