[Caption box:] The Conovaloff family poses for a picture that was taken around 1912 in San Francisco. The white sheet in the background was intended as a backdrop that would cover the side of the house; it came up a little short. From left to right, the Conovaloffs pictured are: Martha, Lukian (the father), John, Mary, Fenya (the mother), Lilian and Alice. Except for mother and father Conovaloff, all are still living. [The last to die in this photo is John, about 1996.] Elite Society MagazineSpring 1982 Pages 86-90, 94 Published in Scottsdale, Arizona, from 1981 to 1984. Story by Bill Coates The political climate makes travel between the United States and the Soviet Union difficult today. Geography made it difficult in 1917. But geography was not enough to discourage the Conovaloffs from leaving the Russian Empire in search of the American dream. Little did they know their search would end near Phoenix. Martha Papin remembers the journey. At the time, she was 12 and her last name was still Conovaloff. Her family lived in Salem, a small farming village west of the Caspian Sea. [At that time Selim was in Kars province, Armenia, next to the Turkish border.] Russian families first settled the Salem area in 1875, the year the Russian Empire took control of it at Turkey's expense. Life in Salem meant three things: family, tenant farming and the church. But this was not the church of the czar the Russian Orthodox Church. Rather, it was founded on the tenets of the Prygun Molokan sect, which the czar never full accepted and on occasion openly persecuted. Even without religious persecution, life was harsh and void of opportunity. Once a peasant always a peasant. So when first reports of the good life in the United States filtered through to the village, the Conovaloffs were ready to listen. And they were ready to leave. [All Spiritual Christians in Kars province were in the middle of the Russo-Turkish war and a falling economy. Some fled to avoid military conscription.] From a nearby city, they boarded a crowded train and headed northwest toward Germany. A week later, the family reached Bremen and booked passage on an American freighter. With a hint of Russian in her English, Martha recalls she had only a vague idea of where the freighter was taking them - - to a country called America. [Pryguny originally arranged to settle in Canada with the Doukhobors who left the Caucasus in 1898-99, but were redirected to Los Angeles by wealthy Russians met by the scouts. For more on the migration from Russia, see Berokoff Chapter 1.] "On the boat, somehow now I know, but we didn't then we got to a place, and it turned out to be Baltimore." The freighter left Baltimore three days later, by which time nearly every one aboard had contracted measles. After a 20-day quarantine in Galveston, Texas, the Conovaloffs set off for San Francisco by train. Just before a scheduled stop in Los Angeles, however, the measles outbreak took its toll on the family; Martha lost an infant brother. [The Selimski group first formed a colony at the north end of the Russian River in Potter Valley just east of Ukiah, Northern California. Within the first year, most realized they got cheated by local people, for example by selling them old chickens that quit laying eggs. Many of the men left the women in Potter Valley to work in San Francisco, from there about half moved to Arizona.] The good life was not to be found in San Francisco. The Conovaloffs entered a town that was still smoldering from the earthquake and fire of the year before. During the 10 years the family lived there, Martha's father, Luke, worked as a laborer and a dairyman. Perhaps life was better than it had been in Salem. But it was still missing the one element Luke Conovaloff deemed most important a farm of his own. "Our family," Martha explains, "they were all from the farm." The opportunity to farm came in 1917. The Conovaloffs and other Russian families in San Francisco were told of irrigated land west of Phoenix. Word came to them from investment companies which wanted to sell the land and the Salt River Project, which wanted to sell water. About 30 Russian families, including the Conovaloffs, got the message and set out for Arizona. [The Selimskii colony (Bogdanoffs, Conovaloffs, Kulikovs, Prohoroffs, Susoeffs, ... settled on one-half a square mile lining what is now 83rd Avenue, from McDowell Road to Thomas Road. They build their own meeting hall, and tried communal farming. Lukian Conovaloff was the presbyter. For more on the Arizona colony history, see Berokoff Chapter 3, or Molokans in Arizona, by Fae Veronin.] Along with two of his brothers, Luke was accompanied by his wife, Fenya; his daughter, Martha (and her husband); and a 7-month-old son named Alex. As brother and sister, Alex and Martha have much in common. They both continue to share in the legacy and traditions left to them by their now- departed parents. But there are differences between them as well. The tale of the Old World is more easily read in Martha's appearance and manner. At 85, she looks every bit the Russian babushka with a small frame and a feisty but endearing personality. Her English is good, but it still contains traces of a Russian accent and dialect. Alex's English, however, leaves no clues to suggest that he can speak Russian fluently, which he can. In English and in Russian as well he is articulate, but down-to-earth. And although he lacks his sister's feistiness, he shares her sense of humor. "I was 7 months old when I decided to settle here," he says. Now 65, Conovaloff continues to run the family's 400-acre cotton farm near 85th Avenue and Thomas Road. His red-brick home sits at the edge of the farm, just a half-mile from the house his sister lives in. Built in 1937, Martha's house borders on American Gothic with a white, wooden exterior and a musty attic and cellar. Unlike his father, Alex Conovaloff did not dream of becoming a farmer at least not at first. He had initially set out to be a lawyer. He got as far as starting his own law practice in Phoenix after he graduated from the University of Arizona law school in 1940. That lasted little more than a year. When his brother died of botulism in. 1942, Conovaloff returned to the farm to help manage the family business. He expected the arrangement to be a temporary one, but it. didn't work out that way. He stayed on the farm. But even there his knowledge of law has continued to be of value to him. And he no doubt has had occasion to fall back on it in the 27 years he's been serving on the Salt River Project board of directors. [Alex died in 1986, and a SRP electrical sub-station was named in his honor on McDowell Road, about 86th Ave, across the road from their farms.] The group the Conovaloffs came with accounted for a

large part

of the Russian settlement outside Phoenix, but not all

of it.

Altogether, perhaps 50 families moved in from the

coast to farm.

Loosely speaking, these families made up the Valley's

Russian

Spiritual

Christian community. The boundaries of this

community ran roughly from Glendale

Avenue on the north to Van Buren Street on the south,

and from 75th

Avenue on the east to just beyond 85th Avenue on the

west. [The

number of households was much

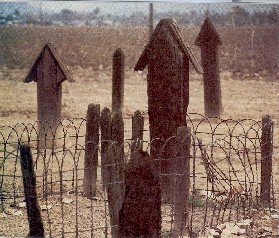

higher.] About the same year the Conovaloffs settled in, the Treguboff family moved to the Valley with a group from Los Angeles. John and Fanny Treguboff purchased 120 acres near Maryland and 75th avenues; here they raised wheat, cotton and a family of 10 children. Right on the comer of 75th and Maryland sits the cemetery in which John and Fanny are now buried along with other Russian immigrants and their families. John Treguboff died in an automobile accident in 1967. He was 87 years old.

His son, Paul, now runs the family farm, Only now the main produce is milk from dairy herds rather than cotton or wheat. And the bulk of the business is now in Buckeye, rather than the Russian community. Paul, however, still lives on the land once held by his father. And like his father, the younger Treguboff possesses the character of a person tied to the land. He is thick-boned and stocky. He has an earthy vocabulary and a hearty, ribald sense of humor. For the 49-year-old Treguboff, the farm is his life, "I'm going to stay on the farm. I don't give a shit. I'm going to die there. I have pride in ownership and pride in what I do." At the time Treguboff was growing up, neighboring Glendale was a community of about 5,000 people. Few of these people spoke Russian. Treguboff did not find that out, however, until he entered a Glendale school. There he encountered a language he regarded as completely alien: English. His first year of school, he says, "was a bitch. I guess it was kindergarten; I couldn't understand anything anybody was saying, so they sent me home." Eventually, though, Treguboff caught on. Throughout grade school he made the honor roll regularly and rarely missed a class. This was not so much because he liked school which he didn't but rather because it meant fewer hours of work on the farm. Not until high school did Treguboff begin to realize that he enjoyed farm work more than homework. Treguboff remembers not only the hardship of farm work, but of life in general during his youth, For many, the greatest hardship was the summer heat. Evaporative cooling let alone air conditioning was non-existent in the Treguboff house. People slept outside during the sweltering summer nights, Treguboff recalls. And to ward away mosquitoes, he says, you lit a bucketful of manure before turning in. The oppressive summer heat accounted for one reason why many Russian families packed up and moved back to the West Coast. The depression of 1920 accounted for another. In Martha's words: " 1919 was a very good crop cotton. Everybody made money. And in '20 they planted more cotton than they could handle. They even sold cows and put in cotton, and then the cotton didn't have any price at all. Nobody would buy it." [During World War II, cotton prices were very high. After the war, prices fell.] Many families who weathered that depression didn't make it through the one that hit 10 years later: the Great Depression. In its wake, only a handful of the original Russian families have remained. And only within recent years has their perseverance begun to pay off at least in terms of dollars. The real money, however, comes not from the crops but from the land itself. This land is now prime real estate. And as the tract homes of suburban Phoenix and Glendale edge ever closer, the land becomes ever more valuable. Treguboff, for one, is thinking of selling off most of his holdings near 75th and Maryland. Conovaloff says he probably will sell off most of his own farm eventually. So the writing is on the wall. Suburbanization will one day swallow up and digest what's left of the Russian community. For now, though, the sense of community runs strong in the remaining families. In the early days of the settlement, this sense of community hinged largely on the church, Conovaloff says. "I think for all the people during those times, life revolved around the church," he says. "It was the center of social activity and religious activity." To some extent, this is still the case. Molokan services continue to be held in a simple, one-story church that has plaster walls on the outside and no steeple on top. Conovaloff and his sister are among those who worship there regularly. But overall attendance has declined in the past few years. That's somewhat understandable. The newer generation of offspring has had more exposure to the world outside. Not only have many abandoned farming as a profession, but many also have left the fold of the church. And many are marrying outside the ethnic group. This would have been unthinkable in 1914, the year Martha married. "At that time, we couldn't even associate with a person from another village. We just couldn't," she says. Even today, Russian families have a word for the non-Russian who marries one of their offspring. "They call them 'ninash,' " Martha says. "Ninash means not ours, not of our group. They say, 'He's a ninash.'" Marrying a ninash, however, is not the stigma it used to be. Nor is taking up an occupation that would remove one from the extended family. Conovaloff, therefore, can rest easy about his older son, Luke. Luke practices medicine in Long Beach, Calif. He is also married to a non-Russian Dukh-i-zhiznik. Martha herself does not fret about the choice made by her nephew. But she does feel an overall sense of loss about the breakup of the community. [The reporter may have confused marrying from another village and moving away as the loss of family togetherness.] "What the old values were to us was sticking together the group, the family, church. Now we're losing that." As she speaks, she points to the example of her own granddaughter, Andrea Adrian. Andrea Adrian, 32, has married outside the group. She also became a nurse. And unlike her grandmother and mother and father as well Andrea Adrian does not speak Russian. Her departure from Russian traditions, however, does not mean rejection of them. Just recently, in fact, she has set out to learn the Russian culture she failed to acquire in her childhood. Her first lessons have come in the kitchen. "A few months ago," she says, "I made borsch for the first time." Conovaloff's younger son, Tim, has taken steps of his own to preserve his family's heritage. Though he did not learn Russian at home, he majored in it at the University of California at Berkeley Arizona State University; UCLAUniversity of California, Los Angeles; Russian House, University of Washington; and CSUNCalifornia State University, Northridge. He also married a woman of Russian descent. And now, Tim, 28, helps his father run the family farm. In addition to that, Tim looks distinctly Russian: with dark eyebrows, penetrating eyes and a ruggedly pleasant face. [This farm was sold in the mid-1980s, is now a sub-division. They were moving their farm to Yuma just as Alex died, so Tim and his mother settled there and eventually rented out their newly acquired land.] Like Andrea Adrian, then, he cares about his Russian heritage. If subsequent generations care also, the tradition of the old country will not easily die out. But there is one thing that will remain buried with the first Russians to settle the Valley one thing they could never have passed on to their descendants, however much they may have wished to. And that was the deep appreciation they had for their new country. In the words of Plaul Treguboff: "For them, this was like dying and going to heaven." |