Dukh-i-zhizniki

in America

An update of Molokans in America (Berokoff,

1969).

IN-PROGRESS Do not cite text without references

Enhanced and edited

by Andrei Conovaloff, since 2013. Send comments to

Administrator @ Molokane. org

Chapter

1 The Migration

[Contents]

[Chapter 2>]

Contents

- Immigration

Updated: 25 May 2017

- Professions Updated: 25 May 2017

- Religious freedom Updated: 25 May 2017

- Arrest of M.G. Rudomyotkin Updated: 25 May 2017

- Pokhod journey to

refuge Updated: 1 Sept 2021

- E.G. Klubnikin Updated: 25 May 2017

- 1886 Census, Kars Oblast

- 1895 Verigin Dukhobortsy Burn Guns

- First Immigrants in Los Angeles,

1904

- What if Canada? Updated:

8 Dec. 2021

1. Immigration

[PAGE 11] The emigration of more than 10 thousand the

Spiritual Christians

Molokan people from

Russia occurred at about the same time that the great migration of

other peoples of Eastern and Southern Europe reached its peak. At the turn of the century (about 1900) Previous

to the end of the 19th and

the beginning of the 20th centuries most of the

newcomers to the new world were from Western

Europe Great Britain, the Scandinavian countries and

Germany. Most of these, with the exception of the Irish who

immigrated earlier, sought to take

advantage of the Homestead

[Act of 1862] Law, enacted in the

1860's to aid in the development of the newly-opened

territories in the Middle West and established

themselves as farmers in the various states and territories west

of the Mississippi River.

However, towards the latter part of the 1800s

19th century the United States were becoming

more and more industrialized. There was great

need for laborers in mines, steel mills, rail roads and the

textile plants of New England and other industries of the

Eastern states.

This development opened up vast opportunities for Eastern and Southern European peasants

the poor of Russia, Poland, the Southern Slav countries as well

as Italy for a change in their hopeless poverty. In addition

there was an opportunity for the Jews to flee from the

oppression and periodic pogroms in Poland and the Tsarist Russia

as also for the Poles to escape political disadvantages from the

same government. The Slavs of the Balkan countries too, sought

to make what was for them a quick fortune from the high wages in

the mines and steel mills of the United States, a fortune that

would enable them to return to their homes and their families [PAGE 12] and to live

comfortably in their old age. The Italians, of course, were

trying to escape the hardships of an over-crowded country and,

on the whole, had no desire to return to the old country.

Millions flocked to the new world, each for his own reason.

Russians, too, came in significant numbers, some for political

reasons, some for economical and some for a combination of

both. See: Why

Did They Wait So Long in Russia? Why Did Most Stay Home?

In a 13 year period (1899-1912), more

than 10 thousand Spiritual

Christians migrated to North

America from the South

Caucasus led by about 1/3 of all Dukhobortsy. The Dukhobortsy migration

is extensively documented in many published first hand reports

(100s

online), more than all other Russian Spiritual Christian

faiths that migrated to North America combined. Although

standardized Canadian spelling is "Doukhobor" and the common

transliterated Russian spelling is "Dukhobor," the

original Russian word is dukhoborets (plural: dokhoborstsy),

and there are 70+ spelling variations in English.

Most readers of Berokoff thought he was

reporting first hand the history of all the non-Dukhobortsy

Spiritual Christians who he mistakenly called "Molokan."

Actually he was just trying to report the history of his

particular Dukh-i-zhiznik faith of Klubnikinisty,

as he wanted it to be told.

What was the actual sequence of events

that brought these various nationalities of peasants from

Russia to the Americas more than 100 years ago?

The omission of the Dukhobor connection

by Berokoff is puzzling because E.G. Klubnikin, presbyter and

prophet of Berokoff's congregation, lived near all Dukhobor

villages in Kars oblast, where he surely knew

about their 1895 arms burning protest, and

witnessed their arrest and exile transport to and from Kars.

All Kars Dukhobortsy

had to travel through his village of Romanovo [this map mistakenly

shows all non-Dukhobor Spiritual Christians as

"Molokans"], past his house, to go to south to Kars city or

north to Tiflis oblast (Georgia). Klubnikin lived in the only

non-Dukhobor

village located to witness most all the local Dukhobor

traffic. The Dukhobor protests and

persecutions aroused the international news, politics and aid

needed to move about one-third of all Dukhobortsy

(~21,000 population) from the South Caucasus to Canada within

five years. By 1899, about 7,400 most of the zealous Dukhobortsy

emigrated to Saskatchewan, Canada, in 7 ships, and they

continued to leave Russia in smaller groups. By 1930, a total

of about 8,800 Dukhobortsy had immigrated to Canada, while two-thirds remained in

Russia.

Though a majority (2/3) of Dukhobortsy

stayed in Russia, many from all the other neighboring

Spiritual Christian faiths also wanted to go to Canada, if the

move would improve their lives and they could pay their own

passage. Scouts were sent by Molokane and Pryguny

to follow the Dukhobortsy to Canada.

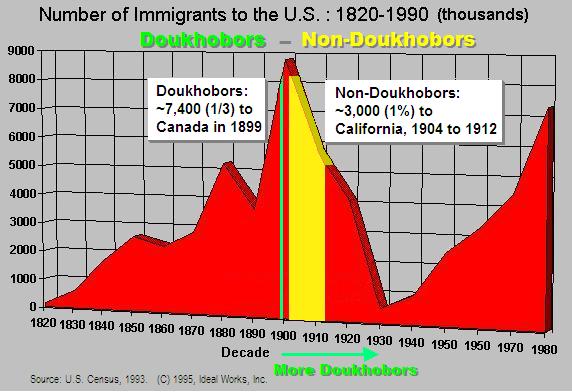

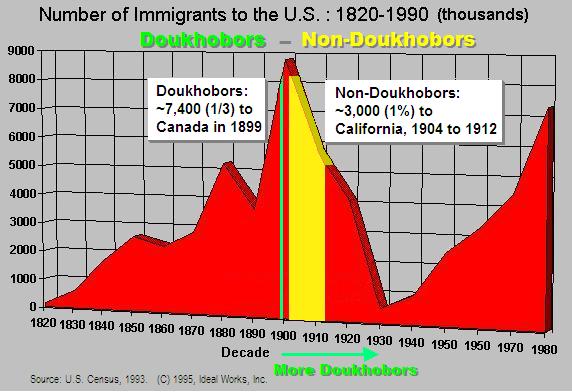

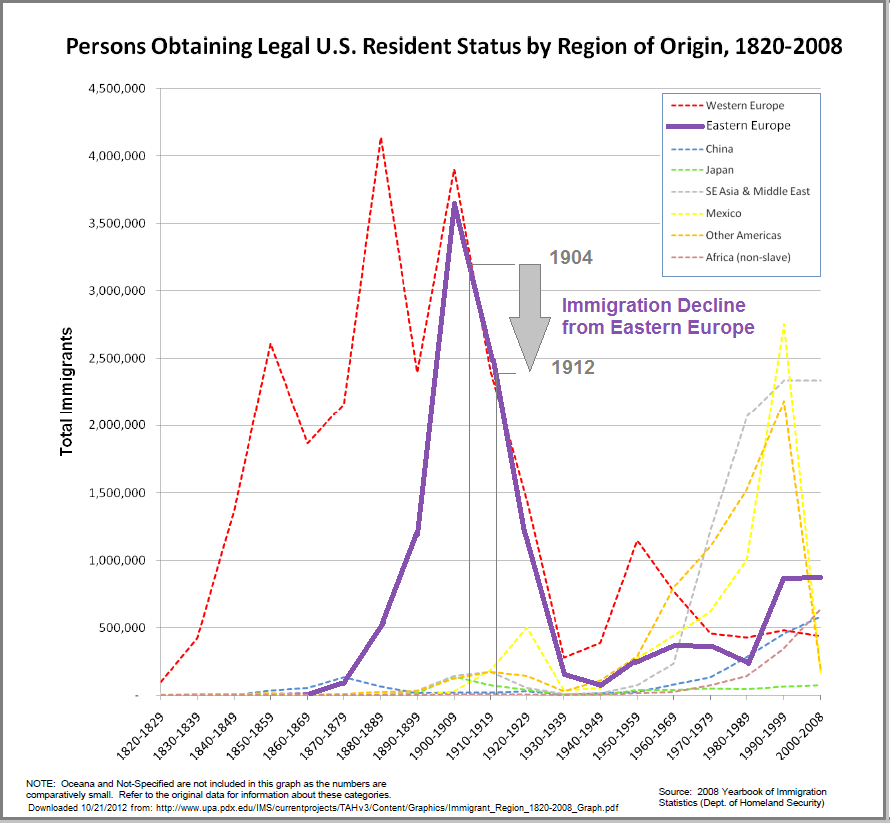

The chart shows total immigration to the United States

from 1820 to 1990. The added colors (green, yellow) show

time ranges of Spiritual Christian immigration from Russia

to north America about 1900, when more than than twice as

many Dukhobortsy (green) arrived in Central Canada

in one year (1899) than all the non-Dukhobortsy

(yellow) in Los Angeles, California, in 8 years (1904 to

1912). By 1930, more than 8,000 Dukhobortsy migrated

to Canada from Russia, compared to less than 3,000 non-Dukhobortsy

to America.

Map source: web.missouri.edu/~brente/immigr.htm

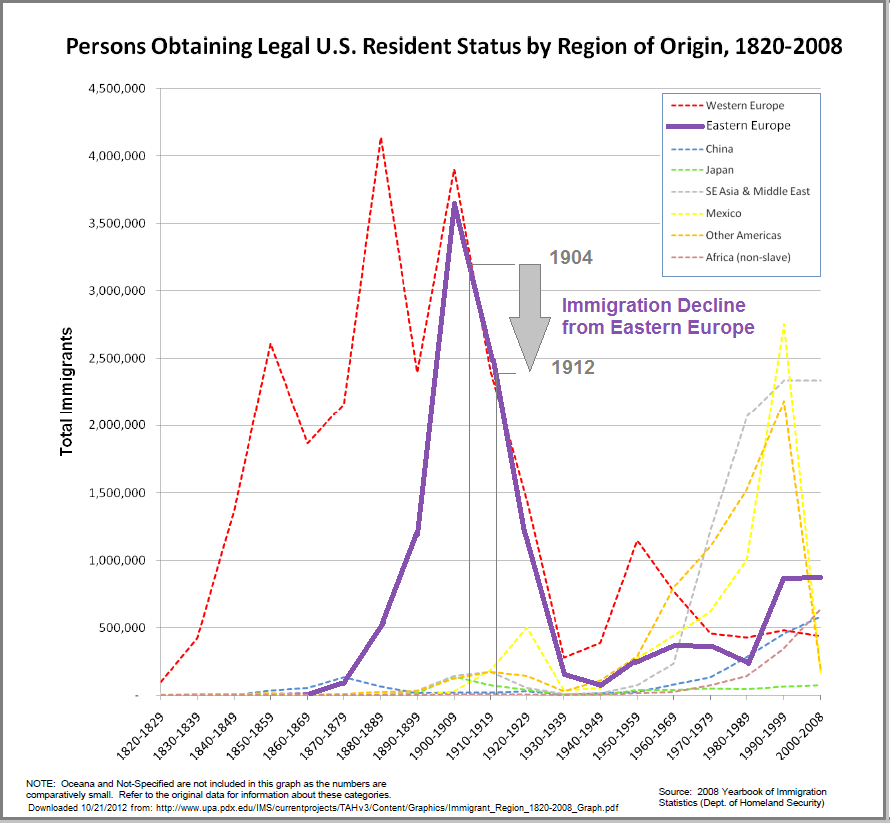

[When U.S. immigration is charted by

regions of origin (below), the policy restrictions for Eastern

Europe can be visualized.]

The

chart shows that non-Dukhobortsy Spiritual

Christians arrived after the peak of legal Eastern

European immigration to the U.S., during the crackdown. By

1918 only 1 of 200 families of Spiritual Christian

families in Los Angeles had "applied" for citizenship.

This chart shows those already accepted as

residents.

Graph source:US

Department of Education Teaching American History Program

(TAHPDX) with Immigration

Act of 1924, Wikipedia

A few Spiritual Christians The Molokans

too, decided at about this time to migrate to the new

world but not for the same reasons as the other people. They

came neither to seek their fortunes nor to find relief from

economic pressure or political disadvantages because at that

time, and for about a half century before that, in fact since

their banishment to Trans-Caucasia in the late 1830's, they were

better off economically than any comparable [peasant] class of people in Russia,

Eastern Europe or Italy.

Most were not "banished" to the Caucasus,

rather the Tsar issued a decree (ukaz)

to give more land to any of his serfs who volunteered to move

to New Russia in the early 1800s, then more decrees about 1840

to resettle in the new territories in the Far East or

Caucasus. Thousands died while

being resettled to the Southern Caucasus. Spiritual Christians

in the Far East prospered the most by 1900.

For a more thorough history of

resettlement of Spiritual Christians from the Russian interior

to the new Caucasus borders, see Dr.

Breyfogle's Ph.D. thesis, book and articles which rely

mostly on government documentation. Doukhobor

Historical Maps, by Jonathan Kalmakoff, Doukhbor

Geenlogy Websitem, should be interpreted to show migrations of

many different Spiritual Christians along with those

identified in the literature as dukhoborsty.

2.

Professions

Being sober and industrious, it did not take them very long

after their arrival in the

Russian-conquered territory of what is now Armenia,

Georgia and other parts of Trans-Caucasia beginning

in the 1830s to build villages

where none existed before, to cultivate grain fields where none

grew before, to establish flour mills along the many streams of

the mountainous country and to plant orchards to supplement

their food supply. And to supplement their incomes they became

freighters (wagon builders and drivers, teamsters,

some used the Russian term drozhky)

during the winter months in a country devoid of railroads, until

1870, or of any other kind of roads, so that at

the end of the century they were quite self-sufficient

economically although, to be sure, there were some poor families

in each village. During the migration and

first years, thousands died of illness due to starvation and

exposure. In 12 years (1834-1846) Molokane in Baku

governate "buried more than 2,000 people, piling 12 coffins

into each grave. Whole families died together, ...." (Breyfogle,

page 91)

3.

Religious freedom

In religious matters too, they were enjoying a fair measure of

freedom for serving as periphery

colonizers for Russia. No one was compelled against his

will to worship God in any manner but his own. Although the

Orthodox Church and foreign churches would,

from time to time, send their missionaries to non-Orthodox

Molokan

villages to try to reconvert them into the state church or a foreign faith, these would be

repelled by self-taught Molokan debaters, but no compulsion was

used and no one was punished for opposing [PAGE 13] the views of the missionaries.

Some Molokane and entire

villages did convert or were altered by Protestant

missionaries Adventist, Baptist, Friends

(Quaker), Lutheran, Mennonite,

Pentecostal, Presbyterian,

Shtundist, etc, and

the new ecstatic Pryguny-Skakuny. Also Spiritual

Christians changed faiths among themselves and with Orthodox.

Many did not know what to name the faith of the rituals

practiced by their family.

4.

Arrest of M.G. Rudomyotkin

(New paragraph) Although the Prygun prophet Maxim Gavrilovitch Rudomyotkin* was imprisoned at about

this time, (1858) it was not for refusing to return to the fold

of the Orthodox church but for daring to petition the Tsar's

Viceroy of Trans-Caucasia for relief of harassment by the local

authorities who were trying at the instigation of the Molokane

Postoyannaye** to put down the new spiritual

manifestation of jumping during religious services.

* Berokoff is writing for Dukh-i-zhizniki

who would know this man's last name, but he is unfamiliar to

most Pryguny, Molokane, and readers

unfamiliar with this confusing history.

** Postoyannie, as used by Berokoff, is an insult

to the original Molokan faith for not changing, or

adapting an ecstatic zealous Prygun faith. (Use

correct labels, Taxonomy of 3 Spiritual Christian

groups). Since 1990, most Prygun congregations in

Russia support the Union of Spiritual Christian Molokans,

and some have joined it as dues paying members. Only Dukh-i-zhziniki around

the world, whose ancestors or predecessors may have been Maksimisty,

continue to insult Molokane. while claiming

their label. In the west (America, Australia), Dukh-i-zhziniki continued to scorn Molokane

for their predecessors' "daring to petition ... for

relief of harassment" from Maksimisty, while

harassing Pryguny with

verbal abuse and shunning for not venerating their Kniga

solntse dukhi i zhisn' and performing

Rudomyotkin's "New Ritual" (novoye obryad).

Most likely Rudomyotkin was arrested for

- being an outspoken leader of a most

undesirable "infectious"

heretic sect,

- trying to convert members of other

faiths to his faith and/ or

- illegally declaring himself a tsar (tsar dukhov : king of

the spirits), which was blasphemy of the Tsar of Russia.

All of these are blasphemy of the

State-Church and prosecuted as serious crimes, felonies.

Nearly all the visible sectarian leaders

were removed from their groups to exile, prison, and a very

few to monastery training. It may be that zealous Maksimisty were

evangelizing Molokane

who did not want to be harassed. If anyone has Rudomyotkin's

arrest documents, please scan and post them, or send them here

for posting so readers can see the facts.

As a matter of fact the churches in the villages and towns were

flourishing as never before. Members were loyal to the faith and

at peace with one another. There were no back-sliders but many illegal converts from the Orthodox

faith. People actively converting Orthodox

to a non-Orthodox faith could be arrested for a felony.

A large neighboring protestant

Armenian village, Karakala

Karakalla, [joined the Prygun

faith became converted to the

Christian Jumpers,

and many most

of whom eventually came to America

at the same time as the non-Dukhobortsy Spiritual Christians

Russian Molokans. Oral history reports that the Armenian

Protestants in Kars oblast were delighted to meet and join the

faith of neighboring Pryguny from Russia, with whom

they felt a spiritual fellowship.

5. Pokhod

journey to refuge

There was much visiting from village to village. The arrival of

a group of visitors from one village to another would be a cause

for celebration. These visits, in effect, would be Spiritual

Christian Molokan revival meetings. There would be

prayer meetings in churches

and in private homes at which time there

would invariably be with

repetitions by Pryguny of

prophecies of "Pokhod" (journey)

to the Refuge. Token flights to the refuge would be undertaken

by marches of a the

whole Pryguny congregation from one end of the

village to the other and back again to the prayer house. These

were called "Spiritual Maneuvers". They foreshadowed the

eventual flight to the refuge in America. Matters concerning the

affairs of the whole Brotherhood would likewise be discussed and

settled at such gatherings. These

"Spiritual Maneuvers" could have been reported as disturbances

of the peace for non-Prygun Spiritual Christians,

especially when Pryguny would aggressively insult

bystanders for not joining their march.*

* In 2012, I interviewed the elder

Bokovs near Seattle WA, whose family were Molokane converted

to Adventism by German missionaries in 1906 in Elizavetpol

governorate, now Azerbaijan. They reported that Pryguny

in their village were "very aggressive" coming

uninvited to their front door, not leaving when told to

leave, and harassing Molokane for not joining the Prygun

faith.

In Canada, Spiritual Christian svobodniki

also performed "Spiritual Maneuvers" between their

settlements and to towns, which were reported in the press,

especially the treks of 100s of people for more than 100

miles. (The 'Sons of Freedom'

a Flashback to 1956, by K.J. Tarasoff, 2009.)

When the first Pryguny and other

Spiritual Christians arrived in Los Angeles, they witnessed 6

weeks (Feb-Mar 1905) of mass

street marches by 2000 American Evangelic Christians to

save sinners, drunks, prostitutes, etc. in the neighborhood

around the Bethlehem Institutions and Chinatown. A large

inter-faith national Protestant convention was being held in

Los Angeles which may have helped launch the "Azusa

Street Revival" in 1906.

But despite the apparent calm and complacency there was a

noticeable undercurrent of a feeling by Klubnikinisty

that their settlement in Trans-Caucasia was not permanent. The Klubnikinist prophets were frequently moved by

the Holy Spirit to remind the people that they should always be

prepared to move to a Place of Refuge (Oubezhisha) (убежище ubezhishche

: sanctuary, haven, refuge).

[PAGE 14] The Prygun prophet

who was the first to utter these words was David Yesseitch who,

as early as the 1830's wrote in his Book of Zion that there

would be separation of the Dukhovny (Духовный

dukhovnyi

Spiritual (Jumpers)) Molokans

into two groups; Zion and Jerusalem, at which time Zion will be

led to a place of refuge and Jerusalem will remain and will be

subjected to a period of tribulation. Of Zion he spoke in these

words; "The Lord will gather all such in good time from all the

countries into a place or refuge where they will be nourished a

thousand two hundred and three score days in all serenity and

quiet." 1260 days = 3.5 years, which if

it began in January 1905, ended in 1908.

Though many American Dukh-i-zhizniki agree by

definition that all Spiritual Christians who migrated to the

U.S. were "Zion," the most zealous continued to insult and

shun Molokane, Pryguny, Subbotniki and Armenian

Pryguny. This

indicates that some of the most zealous Dukh-i-zhizniki may have inherited

oral histories, perhaps altered, to hate all outsiders of

"their" congregation(s) that perform the "New Ritual" of

Rudomyotkin and use his religious text placed next to their

Russian Bible.

This theme was repeated over and over in all the Dukhovny Pryguny and

related faiths churches throughout all the villages in

Trans-Caucasia. (Berokoff apparently

assumes all Spiritual Christians were united in Russia.)

Songs, which generally reflect the yearnings and desires of

people better than any other media, were composed and sung with

fervor, exhorting the people to be prepared for a Pokhod (поход : trek, journey) to the Refuge.

Our present song book is replete with old time songs containing

such exhortations. Among the many are the following numbers: No.

3, No. 140, No. 147, No. 149, but the most famous and most

popular in its day and very much beloved even now was No. 326; [Ne pora li

tebe Sion, Upravlyat' sebya v pokhod.] "NE

PORA LI TIEBE SION OPRAVLIAT SIEBIA V POHOD".

|

"Is it not time for thee

Zion to prepare thyself for Pokhod?

From this terrible menace that is coming so soon

From this northern land it is time for thee to escape,

To a far southern country, a wilderness of peoples,

. . .

There is the Refuge for members sealed to be there,

etc., etc."

|

|

Не

пора ли тебе Сион, Управлять себя в поход.

От ужасной сей грозы, Хотящей скоро прийти.

От Северной сей страны, Время тебе Сион выйти.

В дальнюю Южную страну, В людскую пустыню,

. . .

Там убежище членам, Запечатленным быть там..

|

These songs repeatedly reminded the people that there will be a

flight to the refuge but not from economic want nor from

religious persecution but from a terrible menace that is coming

soon, a menace that was to shake the whole world, the

Apocalypse or the Soviet Union run by Stalin

6. E.G. Klubnikin

No one knew the precise meaning of these prophesies. No one

knew the location of the Refuge nor the exact time of the Pokhod. There was one

youthful prophet however, to whom [PAGE 15] the Holy Spirit revealed the

approximate time of the Pokhod

but not the place, except in very general terms.

Some time around the year 1852 this youthful Prygun prophet,

Efeem Gerasimitch Klubnikin, who was born in 1842, was inspired

to draw prophetic sketches and plans and to write down

prophesies of the flight to the Refuge.

In these revelations he was told that at the proper time three

certain signs will appear by which he will recognize the time

for the Pokhod. He

wrote these revelations down in his boyish hand and telling no

one about them, awaited patiently and secretly for about forty

years for their appearance.

On page 638 of the Book of Spirit and Life, among his other

writings, there appears this prophesy:

Article 5: Concerning the dawn and the

journey

"A plan was drawn. On it were

drawn the numerals 99 and 44, a rising sun and a window. From that

time forth the judgments of God will begin their fulfillment year

after year. Angels of God will be released to torment and punish.

The nations will groan from their calamities. Soon there will be

three signs previous to the flight to the Refuge.

1: The people will gather for prayers in the middle of the night.

2: A light will flash across the heavens at night. It will be seen

throughout the whole land.*

3: At night time, from the cast towards the west, a song will be

sung, 'A cry is heard; Behold the bridegroom cometh'.**

Those who will believe this will make the journey to a far country

but the unbelievers will remain in their places."

* 1853

Klinkerfues comet, or was Klubnikin predicting a later

meteor, below?

** --SONG----

Efeem Gerasimitch was born in the village of Nikitina, in the governorate province of Erevan,

(now in the capital

country of Armenia) on Dec. 17,

1842 only two years after his parents, together with many other

Spiritual Christians Molokans, made

the arduous journey on foot from Central Russia on orders* of the government of Tsar

Nicholas the First. Efeem was the third child in a

large family of five brothers and five sisters. Nikitino was renamed Fioletovo in

1936.

* Most voluntarily migrated to get more

land and military exemption. Breyfogle.

Of his father he wrote; "My father, Gerasim Karpovitch, lived

in Russia in the province of Tambov

in the city of Morshansk.

[PAGE 16] My mother,

Anna, was also from the same province, from the Village of

Algasova". [Footnote: This was also the native village of M. G.

[Rudomyotkin] Rudametkin.]

When my father was 17 years old, he was severely punished for

his Molokan faith. He was given 180 strokes with birch rods and

on the next day again that many, after which he was turned over

on his back and given another 180 strokes so that he could

neither sit down nor lie down. When he again refused to return

to the Orthodox Church the priest ordered the police to bind his

head in wooden stocks and told them to tighten the screws more

and more until he fainted, after which he was made to stand in

the freezing cold for some time and then was sent home". In 1840

his family, together with other families refusing to recant

their Molokan

faith, were banished to Trans-Caucasia and eventually arrived in

Nikitina where Efim was born. [According

to oral history, the Spiritual Christian Prygun movement was

founded in 1933 in New Russia,

now south Ukraine; however, the label "Pryguny" first

appeared in print about 1856 according to Dr. Breyfogle.]

Here the [Prygun] Klubnikin family

lived until the end of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878. When

the peace following this war was concluded, Russia took over the

region around the city of Kars

from Turkey, and, desiring to settle the new frontier with

Russian People, induced many [Spiritual Christian] Molokan families

to move there in the years after 1880. Soon quite a number of [Spiritual Christian] Molokan villages

were established and thriving there, later becoming the center

of agitation to migrate to America [which

was proceeded by 1/3 of the most zealous Anabaptists (mostly

"Mennonites" from Ukraine) in the 1870s, then by 1/3 of the

most zealous Spiritual

Christian Dukhobortsy from 1898 to 1930 (from

the Caucasus)].

There is some DNA genetic evidence among

some Dukh-i-zhznik families who migrated to America

that their ancestors intermarried with Germans, probably

Anabaptists encountered either along the Central Volga or in

New Russia. We know that ancestors of Pryguny borrowed

zealous jumping, prophesy of the Apocalypse, flight to Zion,

and songs from neighboring Anabaptists in New Russia.

The 1886 Kars census (table below) shows

Pryguny were counted as less than 3% of the Russian

settlement population, and nearly all were in Selim

village where my father's family is from and many of the

founding families of the Molokan congregation in San

Francisco. Indigenous and Turk peoples are not shown in this

table.

7.

1886 Census, Kars

Oblast

GROUP

|

Molokane |

Dukhobortsy |

Russian

(Orthodox)

|

Pryguny

|

Subbotniki |

Estonians

(Orthodox)

|

TOTAL

|

| Count |

5,923 |

2,766

|

1,221 |

310 |

306 |

280 |

10,583 |

Percent

|

55.4% |

25.9% |

11.5%

|

2.9% |

2.9% |

2.6%

|

100% |

The 1886 census counted 106 houses in Romanovo

village, population 681, all Molokane. If Pryguny

not in Selim, including Klubnikins, arrived before the

1886 census, they had to falsely claim, or be mistakenly

counted as Molokane. If more Pryguny arrived

after the 1886 census, they intruded upon the many

established Molokan villagers who would have to share

land with the later settlers of different faiths, who sang

borrowed songs not from the Bible and were much more

spiritually zealous. Whereever tribes of Pryguny resettled

they would have held separate Sunday meetings from other

faiths, including different Prygun faiths.

Assuming the 1886 census is probably

correct in that few Pryguny were in Kars oblast

before 1886, the many Pryguny who relocated to Molokan

villages in Kars oblast from their previous homes in the

Caucasus and central Russia came after 1886 to qualify for

military exemption given to colonizers of new Russian

territory. Since Pryguny were the last to arrive and

had some zealous members, they were most likely the

first to seek another settlement area, therefore most likely

to emigrate. Keep in mind that less

than 1% of all Spiritual Christians moved from from Russia

to North America.

The Klubnikin family settled in the new village of Romanovka,

Kars governate (guberniya), Russia (now Yolboyu

village, Qers/Ghars province, Republic of Turkiye). It

was there that Efeem Gerasimitch (Efim

Gerasimovich) Klubnikin later saw the appearance of the

three signs that he was patiently awaiting for so long.

While he was thus waiting, another event occurred that greatly

perturbed some of the Spiritual

Christian Molokan people throughout

Trans-Caucasia. In 1889 the fifty-year period of exemption from

military service granted to all settlers from Russia them at the time of their voluntary resettlement and banishment for some from Novorossiya

(south Ukarine) and central Russia in 1839, had

expired. The Government immediately informed the Spiritual Christians Molokans, through the leading elders

assembled [PAGE 17] for

that purpose, that hereafter their young men of the age of 21

years will be conscripted for a five year period of military

service like any other category of the nation.

Although this decision certainly violated the consciences of

all the assembled elders, they did not offer any resistance at

that time but secretly meant to find ways to evade the order.

About this time Russia pacified the newly conquered territories

cast of the Caspian Sea (Turkestan*)

and, being anxious to settle the region around the new border

with Russian nationals, offered the [colonists] Molokan another

10 year period of military exemption to those who would settle

there. Hundreds of [Spiritual Christian] Molokan families

took advantage of the offer, moving to the newly opened

territory from Armenia, Georgia and from the [governate] region of Kars

and establishing a number of thriving [Spiritual

Christian] Molokan villages

there.

[* In the 1800s, "Turkestan" originally literally referred the

place of

the Turkic

peoples, the general large Middle Asia

area inhabited mainly by Muslims, which included what

became Russian Turkestan and the Kazakh Steppe. This entire area

may be the Tika (East) of which M.G. Rudomyotkin

wrote.]

Others however, sought a more permanent solution to the

question of military service. Conference after conference was

called to find a solution to the problem. In the meantime

certain events transpired that convinced Klubnikin that the

signs he was so patiently awaiting had now appeared. Some time

around the turn of the century, in the villages of Melikoy [(Prokhladnoye)]

and Romanovka, without previous

consultation of any kind, people spontaneously began to gather

in the middle of the night for prayer services.

At approximately the same time a tremendous flash of light had

appeared in the sky.*

Many people

witnessed the phenomenon, awed and mystified by the

manifestation, but being for the most part illiterate, they did

not note the date nor the hour of the occurrence so that now we

are without a written record of the event although many are

alive now who heard of it first hand from their parents.

[Footnote: The Los Angeles

Times of Sunday, Feb. 9, 1969 contained a dispatch from

Chihuahua, Mexico describing a similar phenomena that occurred

in Southwest United States and Northeast Mexico the previous

day. "A blinding blue-white fireball, believed to be a meteor

turned night into day across Mexico and S.W. United States. The

light was so brilliant we could see an ant walking on the

floor", it said. An American astronomer visiting an observatory

in Texas said; "It was extremely bright. We had high clouds in

the area but it burned right through. It was several times

brighter than a full moon".]

[This was the Allende

Meteorite shower. "Meteor-Like

Object

Turns Night Into Day: Blue-White Fireball Seen for 1,000

Miles, Vanishes Over North Mexico's Mountains," Los Angeles Times,

February 9, 1969, page A-10.]

[ * This table shows possible

sources for the "tremendous flash of light" ... "around the

turn of the century"]

|

Date |

Meteorite

name

|

Country |

Distance1

|

Size2

|

|

|

|

1,160 miles

|

|

April 18, 1880

|

Veramin |

Iran

|

590 miles

|

120

lbs.

|

November 19, 1881

|

Grossliebenthal |

Ukraine |

740 miles

|

18

lbs.

|

| February 3, 1882 |

Mocs

(shower)3 |

Romania

|

1,000

miles

|

660

lbs.

|

February 3, 1890

|

Collescipoli

|

Italy

|

1,550

miles

|

|

April 10, 1890

|

Misshof |

Latvia |

1,430 miles

|

13

lbs. |

April 7, 1891

|

Indarch |

Azerbaijan |

200 miles

|

60 lbs

|

September

28, 1891

|

Guκa |

Serbia |

1,160 miles

|

4

lbs.

|

September

22, 1893

|

Zabrodje |

Belarus |

1,220 miles |

7

lbs.

|

July 27, 1894

|

Savtschenskoje

|

Ukraine |

740 miles

|

6

lbs.

|

May 9, 1895

|

Nagy-Borovι |

Slovakia

|

1,290 miles |

13 lbs. |

April 13, 1896

|

Lesves |

Belgium |

2,000 miles |

3

lbs.

|

May 19, 1897

|

Meuselbach |

Germany |

1,690 miles |

2

lbs.

|

August 1, 1897

|

Zavid |

Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

1,250 miles |

209

lbs.

|

March 12, 1899

|

Bjurbφle |

Finland

|

1,550 miles |

728

lbs

|

1899

|

Magnesia |

Turkey |

850 miles |

11

lbs+

|

| July 8, 1900

|

Alexandrovsky

|

Ukraine

|

890 miles |

20

lbs.

|

July 25, 1900

|

Ofehιrtσ

|

Hungary

|

1,160 miles |

8

lbs.

|

August 23, 1900

|

Leonovka

|

Ukraine |

930 miles |

2

lbs. |

[1. Estimated distance measured from

Klubnikin's village of Romanovka

to meteor fall site, rounded to nearest 10 miles.

2. Size converted to pounds from metric (kg., gr.)

3. The

only meteor shower on this list, more than 3000 pieces

collected. In 1866 the Knyahinya

meteor fireball fell ... ]

[PAGE 18] The

third sign also appeared soon after these when in the village of Malo-Tiukma people began to sing a song

whose gist was; "Behold, the bridegroom."

8. 1895

Verigin Dukhobortsy Burn Guns

Berokoff omits the biggest news story of the decade and most

probably the main stimulus for migration fear. In the Summer

of 1895 in the Transcaucasus, Russia, about one-third of Dukhobortsy,

followers of P.V. Verigin who is in exile, quit the military and

burned guns in 3 simultaneous mass protests. Within 3 years ~400 neighboring Dukhobortsy

were jailed, ~4000 exiled, ~2000 died, and ~7400 emigrated.

Klubnikin lived in the only non-Dukhoborets Spiritual

Christian village, Romanovka, on the main highway and witnessed

the prisoners and migrants march past his house to Kars, and

from Kars to Tiflis. (Historic 1895

Burning of Guns: descriptions, selections and translations,

by K.J. Tarasoff, 2009.)

Being fully convinced by now, Klubnikin confided his

secret to some elders who were closest to him in spirit and urged

them to take measures to leave the country altogether as there was

going to be a period of great tribulation in Russia in the very

near future.

This gave the needed impetus to those who were seeking a

permanent solution to the question of compulsory military

service, efforts which in the winter [at beginning] of 1900 culminated in a

decision [by non-Dukhobortsy

Spiritual Christians] to petition the Tsar's government

for a release from the obligation of military service. Four

elders were selected to personally present the petition in St.

Petersburg. Philip M. Shubin and Ivan G. Samarin were selected

from the region of

Kars [governate] and Simon T. Shubin and

Ivan K. Holopoff were chosen to represent the region

of Erevan [governate].

Missing is the fact that a petition was

submitted by non-Dukhobor Spiritual Christians in 1901

to the Canadian Consul, Port of Batum after the first

huge wave of over 7,500 Spiritual Christian Dukhobortsy left

the Caucasus in one year (1998-1999) on 3 ships from the Port of

Batum (Batoum, Batumi). The non-Dukhobortsy

wanted to go to Canada and get the same privileges as the Dukhobortsy.

The petition as quoted in part from page 749 of the Book of

Spirit and Life is as follows "Your Imperial Majesty! In view of

our Christian upbringing, the existing compulsory military

obligation contradicts the faith that we profess. Our youth are

also instructed thusly, but endure it because of fear of

punishment for refusal to obey. Sooner or later they will refuse

to do so. Fearing to bear the suffering for refusal on the one

hand and not wanting to provoke the government to harsh measures

on the other, we ask Your Imperial Majesty to free us from

personal military service. If that is impossible, we ask to be

allowed to leave the country with our families."

[PAGE 19] The delegates after making the long

journey to the capital [St.

Petersburg], returned with a negative reply and in the

spring of the same year, 1900, the Pryguny chose Philip M. Shubin and Ivan G.

Samarin while the [Molokane] Postoyanaye

chose Feodor T. Butchneff to go to Canada to survey the

possibility of migration to that country, supporting them with

signatures representing 1000 people.

Meanwhile Klubnikin took it upon himself to inform the

villagers in the Erevan [governate]

region.

Traveling from one village to another, he confided his

revelations to elders in that area who, in his opinion, were

sympathetic to the cause but being told about others who were

not favorably disposed and fearing betrayal as an agitator, he

returned to Romanovka and concentrated his efforts in the

region of Kars [governate],

not neglecting to inform the Armenian brethren in Karakala

Karakalla that unless they left the country

their people will endure far more in the coming period of

tribulation than their Russian brethren. This warning was heeded

by the majority of the Dukhonvy

Prygun

Armenians and when the time came they followed the latter to

America.

[Footnote: The prophesy concerning the Armenians literally came

to pass in the first world war. When the Turkish army marched

through the area in 1917, they committed unspeakable atrocities

against the Armenian people in all the villages, including Karakala

Karakalla. For that reason the memory of [Efim] Efeem

Gerasimitch Klubnikin is revered among the Armenian Pentecostals Molokans to this

day.] See: Armenian

Genocide

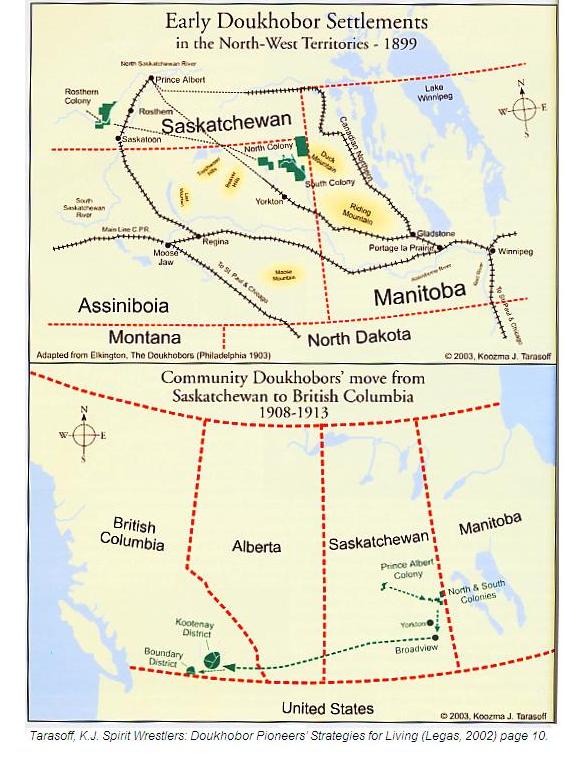

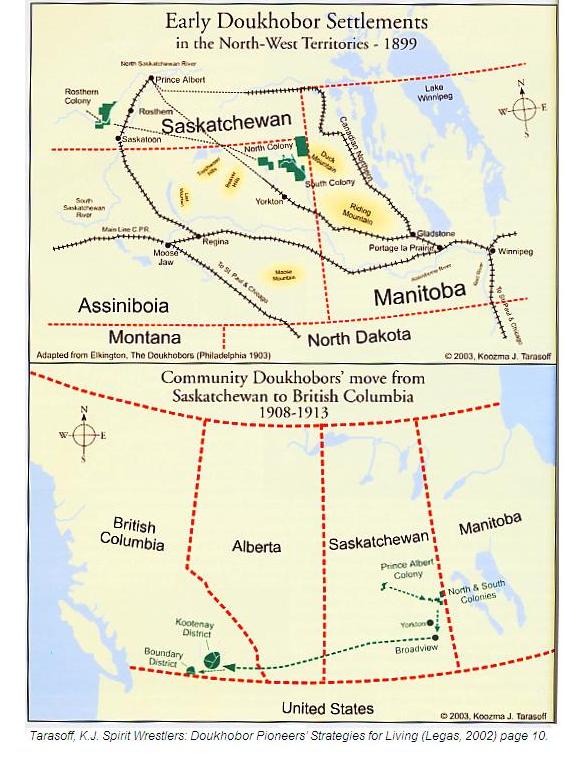

The three delegates meanwhile arrived in Canada and inspected

the Doukhobor

settlements in central Canada [map by Jonathan Kalmakoff] Manitoba as well as

[and] land in other provinces in

the Dominion, at the same time conferring with

Canadian government officials in Ottawa who agreed to grant a

100 year exemption from military service to the non-Dukhobortsy

Spiritual Christians Molokans. After

that they visited several states in the Northwest part of the

United States as guests of railroad company officials who

had surplus land to sell on acceptable

terms.

[PAGE 20] During their

absence another, younger group of men were preparing to leave

for Canada on a similar mission but at their own expense. These

men Aleksei Ivanich Agaltsoff, his three nephews, Mikhai

N. Agaltsoff, Andrei N. Agaltsoff and Vasili I. Holopoff and

Aleksey I. Silvkoff who was not related to the others were

also supported by signatures representing 1000 persons. While

the first group was on their return journey, the younger group

were leaving for Canada in April of 1900. These were to become

the pioneer [non-Dukhobortsy

Spiritual Christian] Molokan settlers in America for they

spent about nine months in Canada and then, upon the advice of a

Russian traveler [Demens?]

whom they met in Winnipeg, moved to Los Angeles where they

secured work laying tracks for the newly-organized Pacific

Electric R.R. Co. at wages of $1.75 to $2.00 per day.

|

|

The four Molokan pioneers in Los

Angeles.

Left to right: Vasili I. Holopoff,* Aleksei

Ivanich Agaltsoff, Mikhail N. Agaltsoff, Andrei N.

Agaltsoff.

Photographed in Winnipeg [Canada] in 1900.

[Photo] Courtesy of John A. Agaltsoff.

Click to Enlarge |

[ * The first man, V.I. Holopoff, spent

five years serving in the Russian cavalry. He settled in Hartline,

central Washington, and worked in Vernon,

British Columbia, Canada. On May 25, 1915 he joined the

Canadian military. See his Attestation

Paper : Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force". On the

back

of the form he wrote in: "Religious Denominations: Other

Protestants 'Brotherhood'

." This may be short for "Brotherhood

of Spiritual Christians." Molokan

Soldier Enlisted in WWI Canadian Expeditionary Force,

Doukhobor Genealogy Message Board, post by Jon Kalmakoff, 5

Mar 2007, with many replies.]

The oldest of this group Aleksei I. Agaltsoff after a stay

of one year in Los Angeles, returned home. Of the remaining

four, Vasili Holopoff decided not to return to Russian while the

other three, after an absence of another year following the

return of their uncle, returned home with a glowing account of

their life in California, its glorious climate, abundance of

work for willing hands as compared to severe winters and poorer

living conditions in the old country.

It is very probable that the report of these young men had

considerable influence in the final decision to make the

migration because the report of the three older delegates was

not unanimous. Although Shubin and Samarin's [Prygun] report was highly

favorable, [F.T.] Butchneff's [Molokan] report threw a damper

on the whole movement. He reported in effect, that America was

not a place for religious people, the climate in Canada too

severe and the Doukhobors were struggling hard to survive. His

report had a decidedly negative effect on the [Molokane]

Postoyanaye

and henceforth they ceased their activities in support of the

migration.

[PAGE 21] Some of the Pryguny

were also swayed by Butchneff's report. However, this did

not stop Klubnikin who continued to warn the people of the

coming calamities in Russia, nor did it discourage Shubin and

Samarin who redoubled their efforts before the authorities for

permission to leave the country en Masse. More petitions were

written and presented to the Tsar in St. Petersburg as well as

to his Viceroy in Tiflis.

The authorities were decidedly antagonistic to these

activities. Nevertheless the resolve to move did not weaken. On

the contrary, growing bolder, the elders decided to present a

final petition containing these statements; "Your Imperial

Majesty! Your rejection of our pleas for freedom from military

service and permission to leave the country not only did not

weaken our resolve, on the contrary, it strengthened out spirit

to continue our efforts until the end ... Therefore we ask Your

Majesty that orders be given to permit us to move beyond the

confines of Russia. We ask Thee as the Tsar and Sovereign of the

people, ruler of the throne of the nation. It is in Thy power to

give freedom to those who labor and are heavily laden".

In response to this final plea Philip M. Shubin and Ivan G.

Samarin were arrested by the civil and police authorities and

confined in jail in the city of Kars as subversive

agitators.

When their followers in the near-by villages heard of this they

gathered in large groups in Kars [ ]

and remonstrated [objected]

before the authorities who, in turn, requested them to disperse

pending the disposition of the case by the higher authorities.

But the people, although quiet, were firm in their demands for

the release of their leaders.

This went on for a few days. Meanwhile, an attorney with a

Molokan background was retained to negotiate their release.

After spending fifty days in jail in Kars, through the combined

efforts of the people and the attorney, Shubin and Samarin were

released. After this incident there was no further interference

[PAGE 22] on the part of

the government and no preventive measures taken to stop the

emigration except that no men of military age were issued

passports to leave the country. But this did not deter the

emigration because men of that age bracket (21) had no

difficulty in crossing the border illegally by being smuggled

across the border into Germany by organized bands of smugglers

for a certain fee, indeed, a number of men already in the Army

deserted their regiments and were likewise smuggled across the

border.

Although the government ceased its interference, the Pryguny

themselves were not yet unanimous in the decision to move. There

was strong opposition on the part of very influential elders as

well as on the part of some very respected prophets who

proclaimed repeatedly that our final gathering place of refuge

was not in America but right there near the base of Mount Ararat

as foretold in the writings of Maxim Gavrilovitch [Rudomyotkin];

that although the [pakhod]

prophesies of Klubnikin will certainly come to pass, it was

their firm conviction that the Omnipotent God will protect

Tiflis people from harm in the face of all calamities.

The actions of these prominent prophets Ivan Mihailovitch

Butchneff of Malo-Tiukma and

Aleksey Semionitch Zadorkin, of Nikitina

to name the most prominent ones-influenced a considerable number

of sincerely devout people who were strong believers in

prophesies but who were torn between their loyalties to the

opposing views.

Others were opposed to the emigration because of their

attachment to their worldly accumulation; while yet others,

themselves influential elders, disliked to subordinate their

prestige to a younger leadership for it must be admitted that

Shubin, Samarin, Agaltsoff and Klubnikin and others prominent in

the movement were in their fifties, too young by [Spiritual Christian] Molokan standards to be leading such an

important movement.

[PAGE 23] This debate

continued in all [Spiritual Christian] Molokan villages throughout

Trans-Caucasia and the Trans-Caspian regions for about three

years or until the beginning of the winter of 1904. [Meanwhile about 30, led by V.G. Pivovaroff,

leave Kars about 1 May 1904 and arrived

in Los Angeles before the end of May.]

It was at this time that the testimony of the recently returned

brothers [Mikhail N. and Andrei N.]

Agaltsoff played such a decisive role. Very early in that winter

a conference was assembled by the elders of the Kars [governate] region in the

village of Novo-Mihailovka where representatives of ten

communities were present, including a leading member of the

Armenian community of [Karakala]

Karakalla, Ardzuman Ivanitch Ohanessian, who

was much respected in the Russian [Spiritual Christian] Molokan communities.

In accordance with [Spiritual Christian] Molokan customs, a three day fast was

declared followed by a prayer to God for guidance. After the

prayers and during the repast, the brothers Agaltsoff were

questioned closely by the elders and guests relative to their

life in America. Evidently their testimony was convincing for it

turned the tide in favor of the migration.

During this repast there was yet another prophesy, a prophesy

which was quickly interpreted by Prygun

Armenian Ardzuman Ivanitch Ohanessian

to mean that the migration must begin but it must begin in

secret, especially from the authorities. This interpretation

was, approved by the whole assembly. Thus the decision was taken

to begin in earnest.

9.

First Immigrants in Los Angeles

On May 1, 1904 the first group of approximately 30 persons, "The Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians"

led by Prygun V.G. Pivovaroff, left

Kars via Tiflis to Batoum where

they boarded a steamer bound for Odessa. At Odessa they

disembarked and took a train for Bremen, Germany where they

again boarded an immigrant ship to New York.

Arriving in New York the group was compelled to split up into

two groups because the larger portion lacked sufficient funds to

proceed to Los Angeles. The smaller group, composed of Vasiley

Gavrilovitch Pivovaroff Pondvaroff

his wife and four children, his brother-in-law, Ivan Ivanitch

Rudametkin; Mihail Rogoff, his wife and two children, proceeded

to Los Angeles where, [PAGE 24]

after a period of two months Vasiley Gavrilitch Pivovaroff managed to arrange credit

with the Southern Pacific Railroad Co. for the passage of the

group stranded in New York. The above mentioned 11 persons, led

by Pivovaroff, are actually the first of the Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians

Molokans to

arrive in Los Angeles for permanent residence. Pivovaroff performed the first

Prygun wedding in

Los Angeles on December 24, 1904. Prygun and

most Spiritual Christian marriages were arranged by parents for a price

and not legally registered until 1912. Following this

group came other small and large groups, the migration gaining

momentum until it reached its peak in 1907.

|

|

A group of Spiritual Christian

Molokan

emigrants in Bremen, Germany awaiting ship to America,

1905.

[Photo] Courtesy of John A.

Agalstoff

Click to enlarge |

Meanwhile, agents for various shipping concerns of Western Europe

were very active in all Eastern European countries, offering their

services and the services of their companies to prospective

immigrants to America. [Competition

increased illegal immigration, drove prices down and caused a federal

investigation in 1907.] The Hamburg-American

Lines of Hamburg,

Germany and the [Norddeutscher

Lloyd] North German Lloyd of Bremen, being the

largest in their field, were able to attract the most passengers.

They became the principal carriers of the [Spiritual

Christian] Molokan

emigrants although several groups [with

little or no money] were induced by other companies to

take the longer route by way of the Black Sea and the

Mediterranean Sea to Marseilles, France

and thence to Panama, crossing the Isthmus by train (it was ten

years before the completion of the Panama canal [in 1914]) and then north along the West

coast of North America by steamer to San Francisco. This route was

so long, involved so many hardships that no other groups willingly

chose it after 1905.

On the other hand, the route through Germany meant crossing the

Atlantic at its narrowest. Going overland by train through Russia,

Poland and Germany, they would embark either at Bremen or Hamburg.

After crossing the Atlantic they would either disembark at New

York or as many did, would stop in Philadelphia or Baltimore to

unload freight and passengers then would continue on the same ship

around the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston, Texas and then by train to

Los Angeles.

Arriving by train in Hamburg or Bremen, they would be quartered in

immigrant barracks belonging to the steamship companies where they

would await the departure of the next [PAGE 25] immigrant ship. These ships sailed to

America at intervals of two weeks.

While thus awaiting, they would have to undergo a series of health

inspections demanded by the United States Health authorities, in

fact the U.S. consular offices in these and other large European

ports maintained their own staffs of doctors for this purpose. In

particular, the prospective immigrant had to show evidence of

smallpox vaccination. If none were showing they would be

vaccinated on the spot. Their lungs would have to be free of any

suspicion of tuberculosis and their eyes would be closely examined

for signs of trachoma.

If the inspecting doctors were convinced that the immigrant was

free from these and other contagious diseases, he was allowed to

board the next scheduled ship hoping that nothing unfavorable

would develop at the examination in the port of entry.

It was at this point that many heart rending scenes of separation

took place because, not infrequently some member of the family

failed to pass the necessary health inspection and was compelled

to return to his birth place, either alone, or if a child,

accompanied by one or both of his parents while the rest of the

family continued the journey to America.

In the nature of things, it was either the very old or the very

young member of the family that would fail the examination.

Measles and small pox in the children and tuberculosis in the aged

was a frequent cause of rejection. Occasionally children would be

confined in a local hospital for further observation and after a

couple of weeks the symptoms would disappear and the family would

be allowed to proceed happily on their journey. But the aged were

usually without hope and would return home with much sorrow and

tears. Occasionally too, persons turned back at this point would

try again after an interval of some months and would somehow

succeed, [PAGE 26] but others would be too

spent or too discouraged to try again and the separation would

become permanent.

For these reasons one large group in the summer of 1907, having

several such rejects among them, decided to heed the advice of

some agents who advised them that they could easily enter the

United States by going to Argentina first and applying for

admission from there, the agents further convinced them that the

journey would not be much longer than via New York. With these

high hopes the whole group sailed on the next steamer for Buenos

Aires.

Arriving in that great city, they discovered to their dismay that

things were not as simple as the agents claimed; that there was

still a lot of red tape to unravel. Seeking an escape from their

predicament, they were advised by some Russian speaking people

that their best solution would be to travel by train to the city

of Mendoza

[, Argentina], at the foot of the

Andes mountains and from there on foot and by pack mule along

narrow trails across the Andes via the 12,640 ft. high mountain

pass to Santiago,

Chili and thence by steamer to California.

After several weeks in Buenos Aires the group, consisting of 70

people of all ages, proceeded by train to Mendoza. Since their

reserve of money was practically spent, they decided to find work

in that city as casual laborers in order to replenish their funds

for the balance of the journey, meanwhile arranging for guides and

mules for the difficult and hazardous trip across the mountains to

Chili.

Three months after arriving in Mendoza they set out on the seven

day journey across the continental divide over the Uspallata

Pass, spending the nights at wayside stations provided for

the purpose by bordering countries and, incidentally burying a new

born baby and losing a guide whose mule lost its footing on the

narrow trail and plunged headlong down the steep mountain side,

killing itself and the guide.

[PAGE 27] Completing this

harrowing journey, the group finally arrived in Santiago, Chili

where, to their great and pleasant surprise, they were met by two

young [Spiritual

Christians] Molokans who were stranded there for lack

of funds and who found work in the city as day laborers.

While in Santiago the group split in two, the majority remaining

there to rest up and to replenish their dwindling funds while

several younger men and women, being more impatient, boarded a

steamer in Valparaiso

and sailed to Panama

where they crossed the Isthmus

by train and proceeded north by another steamer for Vera Cruz, Mexico

and thence by train to El Paso,

Texas where they finally entered the United States three

months after leaving Santiago.

Those who remained eventually wired their relatives in Los Angeles

for assistance and, after burying a woman member of the group who

died there after childbirth, were able to proceed without further

incidents by steamer to Ensenada,

Baja California, entering the United States at San

Ysidro, Calif. some time in the winter of 1908. [Footnote:

This group included the Lydayeff, the Kornoff, Veloff, and

Meloserdoff families.]

Undoubtedly their hardships exceeded anything that other groups

had to endure, perhaps equaling the hardships of the Mormons when

these had to cross the Rocky Mountains in their trek to the Great

Salt Lake. But hard as it was, costly in life and money, it proved

to be infinitely better than the alternative choice of returning

to Russian from Bremen, perhaps to endure the wars, the revolution

and famine that Russia was subjected to after 1914.

As for the steam ships that catered to the

immigrants trade, these were nothing more or less than freighters

whose upper holds were converted for passenger carrying purposes

by installation of double-decked steel bunks arranged in [PAGE 28] sets of four two

bunks end to end, two side by side, with narrow aisles between

each set. Some ships, in addition to the accommodation for the

immigrants, (who were called steerage passengers) had

accommodations for higher paying passengers. These accommodations,

when viewed by the steerage passengers, seemed to be the ultimate

in luxury.

Before the ship sailed, the holds were crammed with steerage

passengers to full capacity. Each ethnic group, as indeed, each

family group, desperately sought accommodations near each other

for the duration of what to them was a new and, perhaps a

dangerous adventure.

The holds soon became a bedlam of noise as mothers tried to

comfort little babies crying from fright in the strange

surroundings deep in the semi-darkness of the hold. Older children

becoming lost, were yelling for their mothers. These youngsters

soon became acclimated to the new scene and were having a great

adventure. Older people would be yelling at each other over real

or imagined wrongs. After a day of sailing, however, as the ship

entered the English Channel, and later the Atlantic Ocean, the

seas became very rough and the passengers became sea-sick,

remaining in their bunks without the strength to make any noise

until the seas became less violent or the passengers became

acclimated to the motions of the ship.

In any case, the results of seasickness plus the smell of crowded

humanity created an indescribable stench. Whenever the weather

permitted, the passengers were all routed out of their bunks and

forced to ascend to the top decks, allowing the crews to clean up

the holds. At the same time the Ship's doctors would inspect the

passengers for signs of contagious diseases. it must be remembered

that the ship's owners were responsible for the health of every

passenger until the very moment when the health inspectors at the

United States port of entry admitted him. In the event any of them

failed to pass the inspection [PAGE 29]

at that point, the ship was contract bound to return the immigrant

to the port of embarkation at its own cost. It was, therefore,

advantageous for the ship to deliver its human cargo in as healthy

condition as possible.

In spite of all precautions, passengers became ill and some even

died during the voyage and were therefore buried at sea in the

same age-old manner as they are buried even today. It is a strange

mystery why ships could not be equipped with mortuaries so that a

misfortune such as this could be more bearable for the bereaved

relatives by making it possible for them to bury their loved ones

at the nearest port.

More than one [Spiritual Christian] Molokan was thus

buried at sea. The only consolation for the bereaved family was

that they were allowed to perform their own burial rites,

selecting some worthy member to perform the rite if no recognized

presbyter was present.

Not all was tragedy, however. There were many occasions of lighter

nature also. Babies were born on board these ships, the mother

receiving excellent care in the Ship's hospital ward. When the

weather permitted them to remain on the top deck there was much

singing of religious and folk songs. Other nationalities indulged

in their own forms of recreation, such as dancing, wrestling and

the like.

Finally the long anticipated day came when the ship entered the

harbor. As the ship approached the dock the passengers were told

to pin their identity cards to their lapels or hang them around

their necks.

All was bustle and excitement. The meager belongings usually

bedding and clothes were tied together, loaded on the backs of

adults and brought out to the top decks. Older children too, were

laden with light baggage, usually tea kettles without which no [Russian] Molokan family

ever traveled.

Immigrants fought for position in line, each family desperately

trying to stay together. As the gang plank was tied to the ship

they began slowly to descend, being herded by guards to [PAGE 30] the many lines where

teams of expert doctors and custom inspectors stood ready to

examine each immigrant individually, passing each family to

especially constructed wire cages and sorting them as to their

destination and condition of health and detaining those whose

appearance showed signs of sickness, also detaining those who

lacked the required $5.00 in cash for each immigrant as expense

money for traveling by train to their destination.

The unfortunate ones who were detained for reasons of illness were

housed in government accommodations such as Ellis Island in New York

harbor and similar places in other ports of entry. There they

would be comfortably housed and fed for the duration of their

stay. If they were denied admission the ship would take them back

to the port of embarkation on the next sailing date. Although

these accommodations were clean and comfortable they were places

of confinement nevertheless because no one was permitted to leave

them until the final disposition of their application.

Eventually, after weeding out the whole complement of passengers

consisting of between 2,000 and 3,000 persons, all but very few

were allowed to proceed to their future homes in the new world.

The rejected ones, alas, had to return to Europe to face an

uncertain future, separated from members of their family and

friends, completely broken in spirit and ruined financially.

The [Spiritual Christian] Molokan migration

continued until 1912. Only a few families arrived in that year.

None arrived in 1913. Perhaps more would have come in following

years but the outbreak of the war m Europe in the summer of 1914

closed the gates to the United States completely. Never again

would they open as widely as formerly. At the end of the war, in

1921, the United States Congress, to discourage the entrance of

immigrants from Eastern Europe, passed a law restricting their

numbers by a [PAGE 31]

quota system which favored the immigrants of Western Europe

against those from the East [, Immigration

Restriction Act of 1921].

But even this law would have permitted the entrance of a small

number of immigrants from Russia but the Soviet government in its

turn prevented the emigration of anyone from the confines of its

borders, therefore the year 1912 could be considered as the

termination of [Spiritual Christian] Molokan migration

and from that year until 1950 no personal contact was possible

between the [Spiritual Christians] Molokans in

America and their brethren in Russia with one

exception.

In 1922, after the Bolshevik Revolution and after the civil wars

in Russia, several [Molokan] families in

San Francisco formed a cooperative [Kalifornia

village, Tselinskii

District,

Rostov Oblast] and returned to the Soviet Union

intending to live there permanently. But after about five years

they became disillusioned with their life in the new paradise. [Most] They were able

to return to the United States only on the strength of the fact

that each family had one or more children among them who were born

in the United States, therefore, being citizens of. U.S. they and

their parents could legally claim the right to enter the United

States outside of the quota system. In 1927 [most]

they all returned bringing the first personal

stories of the wars, revolution and the terrible famine of

1921-1922.

10.

What if Canada?

What if all Spiritual Christians from Russia

migrated to Canada as originally planned to follow their

neighboring Dukhobortsy?

If Peter A.

Demens did not intervene, the immigrants could have

secured land reserves in Canada, like

the Dukhobortsy did, in addition to military

service waiver they got in 1899. William Prohoroff III

referred to Demens as a demon (devil)

Those who claimed to be Dukhobor or "Molokan"

upon entering Canada would get the same privileges military

exception, bloc land grants, and their own Russian schools. Of

these three promised privileges schooling was the most contentious.

Soon after Dukhobortsy arrived in Canada, they divided

into three major new groups, and the Canadian policies

regarding colonizers changed, which affecting each group

differently. The most zealous svobodniki

(similar to zealous Maksimisty) rebelled against all

education and wanted to return to Russia. I suspect that some Maksimisty

would have joined them or vice versa.

The communal Dukhobortsy, organized as the Christian

Community of Universal Brotherhood (CCUB) led by P. V.

Verigin, somewhat tolerated the Canadian schools,

especially those volunteered by the Society of Friends

(Quakers). And, the independent Dukhobortsy fully

accepted public schools. For details see: Lyons, John. "The

(Almost) Quiet Revolution: Doukhobor Schooling in Saskatchewan",

Canadian Ethnic Studies (Vol 8, No. 1) 1976.

The Dukhobortsy got their land for

no charge because immigrant labor was desperately needed. About

1206

square miles about 1 square mile per family

was given for Dukhobor settlement in Canada in 4

blocs in central Canada . Due

to the intolerable demands by the svobodniki, the CCUB members abandoned

all their land grants and moved to British Columbia, followed

by most of the svobodniki. The independents stayed.

They got 4 times as much land as they would have gotten

under the Dominion

Lands Act 160 acres per applicant for a $10

administration fee (6.25 cents/acre), cultivate at least 40

acres and build a house within three years.

Map by Jonathan Kalmakoff, Doukhobor

Heritage Website. See detailed

maps.

If the non-Dukhobor Spiritual Christians also got 1

square mile per family for settling in Canada, how much

land would they have gotten?

Let's estimate. At least 2,000

non-Dukhobor Spiritual

Christians immigrated to Noth America. If we estimate about 5

people per family (2000/5), we get about 400 families,

and about 400 square miles. So let's compare the Dukhobor

land area to that of the non-Dukhobor land, and

assume everyone stays together.

They would not have met the Dr. Rev Dana W. Bartlett, or Peter

Demens, or Paul Cherbak, or Pauline Young. There would not have

been large agricultural colonies in Baja California or Arizona.

There would not have been a need for a UMCA to address juvenile

delinquency. Every family would have first been farmers, no

rubbish collectors or recyclers. Ice hockey would replace

surfing and football. Everyone would know how to sing "O,

Canada". Some would go south in the winter as "snow birds".

After getting to know many of the svobodniki (Sons of

Freedom, Freedomites) in British Columbia, I often wondered: Would the svobodniki and Maksimisty

have join forces and marched together in 1902?

[<Contents] [Chapter 2>]

Spiritual

Christian History

Spiritual Christians Around

the World