|

|

Spirit JumpersThe Pryguny

Therese Adams Muranaka, San

Diego Museum of Man, Ethnic Technology Notes

No. 21, 1988. |

| This 16-page booklet was

published for "Saddles

and Samovars: Diverse Cultures of Baja

California," a display shown

at the Dan Diego Museum of Man

for 9 months, from July 1988 through March

26, 1989. Showcased were some of

the 4,000+

artifacts that Muranaka (right) excavated

in the colony, many from outhouse pits, for her

PhD

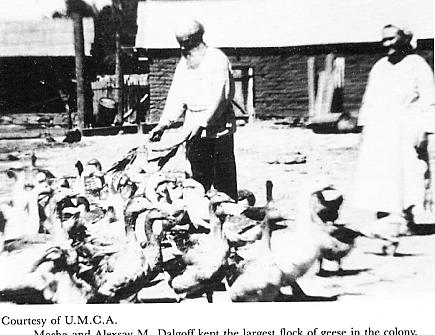

thesis. The state of

Baja

California loaned the items. About 20 Dukh-i-zhiniki

attended the preview opening, and we sang 2

songs led by John & Ann Mendrin, Downey CA. Though Muranaka astutely titled this booklet "Spirit Jumpers," she was misinformed, like all journalists and scholars before her, by the false label "Molokan" extensively used in all of her English citations, and by misinformed informants. Corrections are added here in red some 25 years after publication of the booklet, in 2016. Similar errors occur in the references below and her thesis: Muranaka, Therese Adams. "The In 1995, Muranaka's work inspired George Mohoff, who grew and married up in the Guadalupe Valley, and moved to Los Angeles, to publish the most extensive resident-written book about the Spiritual Christians from Russia in Mexico: The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Molokans in Mexico, with many similar errors and omissions. |

|

In ancient

times, it is shown in the Old and New Testaments the

movements of people from one land to another — like

Abraham, Izaac, Jacob, Moses and others — and of their

worthy trials and tribulations before God [Shubin 1963:2].

In ancient

times, it is shown in the Old and New Testaments the

movements of people from one land to another — like

Abraham, Izaac, Jacob, Moses and others — and of their

worthy trials and tribulations before God [Shubin 1963:2].

Tanya Shubin [right] watched out the window as

the train coursed on and on through the tropical jungle

and oppressive heat. For a young girl from the mountainous

lands of Armenia, the tropics of Panama with its strange

birds and mammals were intriguing and unusual and hinted

of the strange lands she and her family of Spiritual Christian Russian

peasants from Russia would

see as they made their way to freedom. Carrying only a

small satchel of the plain clothing she wore as a Prygun Molokan

or Spiritual Christian

Jumper, she

pondered the events which had led to this flight of her

family and the other Spiritual Christians Molokans

to the New World and wondered where the Spirit would lead

them next.

Many years ago, a group of Spiritual Christians from Russia

Before large numbers of Spiritual Christians began to arrived in Los Angeles, international news reported 200,000 were on their way; equal to the population of the County, and twice the city population at the time. About 1% of that number actually arrived, but nobody would know that for 5-10 years. This news alerted officials to divert them as quickly as possible away from the city.

Attorney and investor Donald Barker, and others, were heavily invested in Baja California, which they expected to be annexed to the U.S. Barker was probably contacted by educated Russians, Demens and de Blumenthals organized to advise and divert the immigrants. As the first waves were arriving in January 1905, some were escorted to Mexico by summer, particularly those led by P.M. Shubin, who also inspected with others much of the US and Mexico as a prospective colonizing client of several railroads. Several families stayed in Guadalupe Valley probably to test the area for living, then others came. Some immigrated via Panama, then Mexico, and were not allowed into the U.S..

For other Spiritual Christian faiths who rejected living with those congregations bound for Mexico, Demens arranged for hundreds to move to Hawaii in 1906. 110 went but returned within 6 months. Though Shubin scouted Hawaii, he never returned but scouted Texas and other locations.

In Los Angeles, Barker appears to have acted as a broker-agent who got a loan from a Los Angeles bank to buy public land from Mexico ($2/acre), to buy supplies requested by colonists (add 85% to the loan), to build one of the 3 flour mills in Ensenada, and arranged for each colonist to pay for his land and share of communal supplies with wheat delivered to the mill. Each colonist appears to have paid earnest money at $50 per share to secure a membership in the commune. The rest of the loan was payable in wheat, or cash, as the member was able. All accounting was done at the Barker mill in Ensenada, which was one of 3 flour mills in the city. The loan was paid in the 1930s.

These people were known as Pryguny (Pry-gun-ny)

Figure 2. Kars and vicinity, origin of this Prygun the

|

|

The Pryguny

|

|

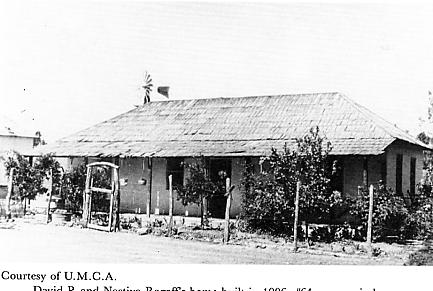

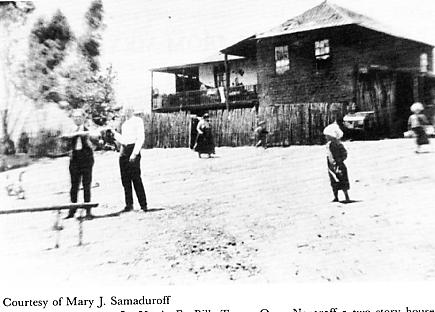

Interiors varied considerably throughout the colony's history. Both of the two rooms, the kitchen and "living" rooms, had feather beds in them; as late as 1960, they had huge storage chests still containing blankets made in Russia but U.S. or Mexican-made sheets (Story 1960:36). Wood, and later gas, stoves, benches built in the walls, kettles mixing bowls, coffee pots, short clear tea glasses and china saucers, wooden spoons and bowls furnished the interiors (H. Rogoff 1988). The Russian samovar [brass urn, wood-fired water heater] or tea service and a Bible, always open, were on display. They did not use the new Kniga solntse, dukh i zhzin' (Book of the Sun, Spirit and Life) created in Los Angeles in 1928, nor adopt the new rituals imposed on all Pryguny in the U.S.. Wedding pictures, perhaps a colored print of the Last Supper, and a Victrola might have been allowed in later years (Story 1960:38, Montemayor 1980). Porches were edged with carved wooden railings, unlike the Mexican houses.

|

|

No elaborate meeting hall

In keeping with

Prygun

In keeping with

Prygun As dictated by the religion, all harvests were held together and the food was stockpiled and distributed by elected elders. Everything was produced on the individual homestead with the exception of coffee, sugar, salt, and rice, which were purchased in Ensenada or San Diego (M. Rogoff 1983). Daily food was plainly prepared and featured a Russian meat soup [vegetable] or borshch, lapsha or noodles, and loaves of wheat bread from outdoor ovens. The Pryguny

* Original quote from: The Works of the Emperor Julian, Volume 1, by Julian (Emperor of Rome), translated by W. C. Wright, 1913, page 495. — Written in 300s. Julian the Apostate was Roman Emperor from 361 to 363, not Jewish and mostly vegetarian.Pryguny, the name for these settlers, comes from the characteristic jumping of a few anointed members, who often raise both hands during meetings, indicating contact with the Holy Spirit, which typically starts abruptly, sometimes with a shout and stomp, then continuing with body swaying, foot stomping, and hopping, skipping and/or leaping, sometimes from their standing position moving toward others for conformation of the Spirit and around the room. Their jumping is somewhat similar to Pentecostalism. Each Prygun congregation has at least one prophet(ess) and anyone may feel the Holy Spirit and jump at any time, which distinguished their form of Spiritual Christianity in Russia. After settlement in Mexico, these Pryguny did not participate in the "Azusa Street Revival" like some of the varieties of Spiritual Christians who remained in Los Angeles. When the new holy book, Kniga solntse dukh i zhin' (Book of the Sun, Spirit and Life) was finalized in 1928, it was not placed on their altar table in Mexico, as it was in Los Angeles, therefore the congregation in Mexico did not convert to a Dukh-i-zhiniki faith. When most Pryguny in Mexico moved to the U.S., if they wished to fellowship with the Americanized Spiritual Christians, they had to join Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations and accept the new book and rituals. No Mexico Prygun families moved to northern California and joined Molokane. Because much of their services are similar in Russian with Dukh-i-zhizniki, many fluent in Russian could participate in the U.S. Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations while privately not entirely embracing these new religions, else they could attend if they followed the rituals without speaking.

To understand who the Pryguny

Splintering, rejoining and splintering again, raskolniki such as the Old Believers were divided in two categories: popovtsy (those with priests) and bespopovtsy (those without priests) (Fadner 1967:755). Molokans are a priestless sect which first appeared in the historical record about 1765 after a split with the Doukhobors,

Under Uklein's leadership, the sect spread from Tambov to Voronezh, to the Cossacks on the Don River, to Saratov, and from there to the Caucasus with Isaiah Ivanov Krylov and across the Volga River with Peter Dementev. Further expansion was noted in Vladimir, and to the area of Ryazan under a follower named Moses the Dalmatian (Conybeare 1962:291).

Doctrinal divisions existed among the many Spiritual Christian faiths —

The practice of jumping and prophesy varies extensively among congregations. At least one person may stomp his/her foot, standing in place with hands raised, for a short time at the height of singing, sometimes uttering a prophesy. In very charismatic congregations, now only among Dukh-i-zhizniki, everyone, including children, must jump to exhaustion with prophesy.

Religious persecution started each time the displaced Spiritual Christian

Fleeing in all directions, perhaps 3,500 people from many Spiritual Christian groups migrated to the United States (Samarin 1982:753), departing by way of Hamburg or Bremen and entering at Ellis Island or Galveston, or via the Isthmus of Panama. Most of the non-dukhoborsty

In the 1920s, when Spiritual Christians moved east across the Los Angeles River and congregations had room to divide, and perhaps a thousand returned to the city after fleeing during the bride-selling scandal (1911-1915), each congregation tried to have their own store, 15 counted, which was labeled by the name of the proprietor — Shubin's Market, Klubnikin's, Metchikoff's, etc. Also the congregations were named by the dominant village of the members, or the surname of the presbyter (presviter); for example, Romanovsky sobranie (village) was also called Klubnikin sobranie (presbyter), among other nicknames which changed over time and division.

Modern-day events have been

difficult for the Pryguny

Modern-day events have been

difficult for the Pryguny

* P.M. Shubin (1850- 1932) resided in Los Angeles, not Mexico. Few, if any, of his relatives were buried there. Only one Ignatsz Schubin is listed, who moved to Arizona in 1916.The first major emigration from Guadalupe took place in 1912*, when an unknown number of settlers departed (Schmieder 1928:421). Dissatisfaction with the land or fear of the uprisings in Northern Mexico during the Mexican Revolution (cf. the pacificos in Reed 1983:57) may have been the causes. Certainly popular folklore cites more than one raid by the Villistas of Pancho Villa looking for food, clothing, and horses (M. Rogoff 1983, J. A. Samarin 1988).

* Probably in January 1916, when all 110 members of the Tiukma congregation left for the Chino Valley of Arizona, led by V.G. Pivovaroff and A.N. Abramoff presbyter. (Dzheromskiy Colony Arizona 1916, by Andrei Conovaloff and Mike Rudometkin, updated : 17 June 2016.)

In 1926-1928 some leaders in Mexico, including Pivovaroff, were trying to make arrangements to migrate to Canada, but they needed financing and enlisted interest from a few Pryguny in Los Angeles. In 1928 delegates from both settlements areas were escorted to Canada, with plans to migrate, and shown property in Alberta where they were offered a block of about 60 square miles east of Calgary near other immigrants also from Russia — Spiritual Christian Dukhoborsty and Anabaptists (Mennonites). Resistance from businessmen established in Los Angeles appears to have cancelled the offer. (Prygun pokhod to Canada, 1928)

The second major exodus from the valley took place after the creation of the ejido El Porvenir in Guadalupe Valley in 1937. Article 27 of the Political Constitution of the United States of Mexico of February 15, 1917, says, "The ownership of lands and waters ... is vested originally in the nation which ... has the right to transmit title thereto to private persons ... the nation shall have at all times the right to impose upon private property such restriction as the interest may require ... in order to conserve and equitably distribute the public wealth" (Deway 1966:52). Elaborated in the Agricultural Code of Mexico, these laws gave President Lazaro Cardenas the right to reapportion tracts of land above a certain size to the general population, a procedure known as the ejido system (Meyer and Sherman 1979:378). ["Can I buy "ejido" land?", by David W. Connell, Connell & Associates, 1998: "...since the constitutional reforms of 1992 ejido land now can be converted into private property and sold to third parties, including foreigners."]

On September 19, 1937, the Mexican government requested a dotación or "donation" and on November 28, 1937, reapportioned 2920 hectares adjoining the colonia to 58 Mexican ejidatarios. The ejido, known as El Porvenir ("things to come"), did not incorporate Prygun

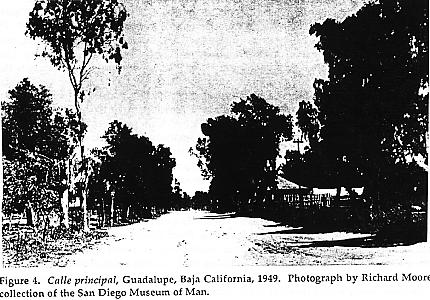

The final change for the colony came with the completion of a new road in 1958 (Deway 1966:82, Story 1960:162, Kvammen 1976) and with the coming of squatters who claimed portions of the valley as their own. The year 1958, in particular, was an election year and activists of the General Union of Mexican Workers and Peasants (UGOCM) were organizing takeovers of private properties to speed land reform (Deway 1966:80). Associated with this movement, 3000 workers appeared in the Guadalupe Valley during the night of July 10,1958 (San Diego Union July 12, 1958 to July 11, 1959). Known as paracaidistas or "parachutists" for their sudden appearance "from the skies," they formed the poblado Francisco Zarco (cf. Meyer and Sherman 1979:385-386) at the fork of the calle principal and Mexico Highway 3 (the Tecate-Ensenada highway). Backed by the Ley de Tierras Ociosas ("Law of Idle Lands") of June 23, 1920, the squatters were attracted by fallow Prygun

More than 1000 acres on the east side of Ensenada was taken by the government from Vasili Kondratovich Popoff, to expand the city. He argued that part of his land be given back as a private Spiritual Christian cemetery, which was granted.

Mohoff said that he believed most Prygun families, like his, abandoned Mexico for California for economic disparity reasons. He said that during WWII one of his friends, who left the Valley to find work in Los Angeles County, returned within the year driving a car. The local boys did not believe their friend actually earned enough to buy a car. "If I worked my whole life in Mexico, I would never earn enough to buy a car!" exclaimed Mohoff. "When we were convinced he was telling us the truth, we all wanted to go to Los Angeles!"

Japanese, Chinese, and Jewish settlers, among other ethnic groups, bought property from the original squatters as time went on, completely changing the ethnic character of the village. Today only one family of rusos puros or "pure Russians" exists in the colonia and six or seven Pryguny

All that is left is a colony in ruins. Residents claim that in ten years no Prygun

For ye have not received the spirit of the

bondage again to fear; but ye have received the Spirit

of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba, Father. The Spirit

itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the

children of God, and if children then heirs, heirs of

God, and joint heirs with Christ; if so be that we

suffer with Him, that we may be also glorified together,

for I reckon that the sufferings of the present time are

not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be

revealed in us [Shubin

1963].

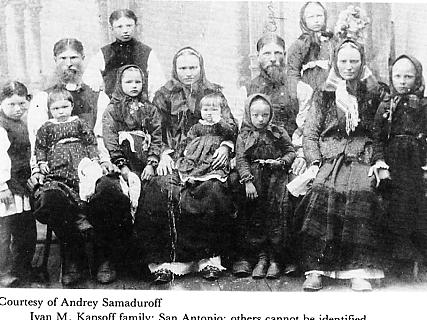

Figure 9. Unidentified Prygun

Later this photo was labeled: "Ivan M Kapsoff family, San Antonio.... "

Acknowledgements

I remember my first trip to Guadalupe with Elena Teresa Orozco and trying to look inconspicuous driving down the main street in a white Mercedes-Benz with Alta California plates.I remember catching my breath at Dukh-i-zhiznik

I remember making Judie Dolbee stand still for 20 minutes in the worst part of San Diego so I could take her picture for a series of Dukh-i-zhiznik

I remember the half hour spent in phone conversation with Dr. Leiand A. Fetzer, Professor of Germanic and Slavic Studies at San Diego State University, and my feeble attempts to spell "Bibaiv [sic]," "Bibaev," "Bibayeff," now "Bibayoff."

I remember taking a "shortcut" on our way to Guadalupe with Helen Long balanced in the back seat of a '67 Volkswagen so that we could see her ancestral home.

I remember Irma Retana's careful translations of Spanish documents while her family ate dinner without her.

I remember the hospitality extended to strangers by the Hector Fuentes family of Guadalupe.

I remember the patience of my husband Jason Muranaka and my son Jay-Michael, which knew no bounds.

Therese Adams Muranaka

San Diego, California

July, 1988

San Diego, California

July, 1988

References Cited

| Conybeare, Frederick C. | ||

| |

1962 | Russian Dissenters. New York: Russell and Russell, Inc. |

Desatoff, Tanya |

||

| 1977 |

Tape recorded interview [original colonist]. Woodburn, Oregon, April 24, 1977 | |

Deway, John Sanford |

||

| 1966 | The Colonia Rusa of Guadalupe Valley: A Study of Settlement, Competition and Change. M.A. Thesis (Geography), California State University, Los Angeles. | |

Dolbee, Judie |

||

| 1983 | Personal

communication [Tanya Shubin Desatoff's

granddaughter] |

|

Dunn, Ethel |

||

| 1970 | Canadian and Soviet Doukhobors: An Examination of the Mechanisms of Social Change. Canadian Slavic Studies 4(2):300-326. | |

Dunn, Stephen P., and Ethel Dunn |

||

| 1978 | Dukh-i-zhizniki

Molokans in America. Dialectical

Anthropology 3:349-360. |

|

Fadner, F. L |

||

| 1967 | Russian Sects. In: New Catholic

Encyclopedia, Volume XII, pp. 753-756. The Catholic Encyclopedia: Raskolniks |

|

Goldbaum, David |

||

| 1971 | Towns of Baja

California: A 1918 Report. Translated with

introduction and supplemental annotations by William

O. Hendricks. Glendale, California: La Siesta Press. Book Review by Dr. W. Michael Mathes, Associate Professor of History at the University of San Francisco. The Journal of San Diego History, Spring 1972, Volume 18, Number 2. |

|

Klibanov, A.I. |

||

| 1982 | History of Religious Sectarianism in Russia (1860s-1917). Edited by Stephen P. Dunn, translated by Ethel Dunn. Oxford: Pergamon Press. | |

Kolarz, Walter |

||

| 1961 | Religion in the Soviet Union. London: Macmillan, and New York: St. Martin's Press. | |

Kvammen, Lorna |

||

| 1976 | A Study of the

Relationship Between Population Growth and the

Development of Agriculture in Guadalupe Valley, Baja

California. Mexico. M.A. Thesis

(Anthropology), California State University, Los

Angeles. |

|

Lane, Christel |

||

| 1978 | Christian Religion in the Soviet Union: A Sociological Study. London: George Alien and Unwin. | |

Lisizin, Francisco |

||

| 1984 | Secta religiosa molokan y la Colonia rusa de Guadalupe, Ensenada, Baja California. Unpublished manuscript. [The Molokan religious sect and the Russian colony of Guadalupe, Ensenada, Baja California] | |

Long, Helen |

||

| 1983 | Personal communication [descendant of Jose Matias Moreno, who owned the Ex-Misión Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe land grant]. | |

Meyer, Michael C, and William L. Sherman |

||

| 1979 | The Course of Mexican History. New York: Oxford University Press. | |

Montemayor, Robert |

||

| 1980 | Baja's Russian Colony Dwindling Away. Los Angeles Times, February 10,1980, p. 2:10. | |

Moore, William Burgess |

||

| 1973 | Dukh-i-zhiznik

|

|

Post, Lauren C., and Carl Lutz |

||

| 1976 | The Prygun |

|

Rangel, Jesus |

||

| 1983 | Russian Emigre Group Fading in Mexico. San Diego Union, June 20, 1983, pp. B-l and 2. | |

Reed, John |

||

| 1983 | Insurgent Mexico. Penguin Books, Ltd. [1914 original is online.] | |

Rogoff, Hanya |

||

| 1988 | Personal communication [Guadalupe Valley Molokan]. | |

Rogoff, Mary |

||

| 1983 | Personal

communication [Guadalupe Valley resident since

1919]. |

|

Samarin, Ivan G. |

||

| 1982 | Dukh i Zhizn' [Spirit and Life]. Third Edition. Los Angeles. | |

Samarin, John A. |

||

| 1988 | Personal communication | |

Samarin, John J. |

||

| 1988 | Personal communication | |

San Diego Union |

||

| 1905a

1905b 1958a 1958b 1958c 1958d 1958c 1958f 1959 |

Issue of August 26,

1905, p. 1, col. 6. Issue of September 5,1905, p. 7, col. 6 Issue of July 12,1958, p. 1:4. Issue of July 13,1958, pp. 1:4-5. Issue of July 14,1958, pp. 1:6-7. Issue of July 15,1958, pp. 5:1-2. Issue of July 16,1958, pp. 5:1-2. Issue of August 8,1958,0.5:1. Issue of July 11,1959, p. 5:1. |

|

Schmieder, Oscar |

||

| 1928 | The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Valley. Lower California Publications in Geography 2(14):409-434. | |

Shubin, Peter Phillip |

||

| 1963 | Untitled manuscript. Los Angeles, California. | |

Sokoloff, Lilian |

||

| 1918 | The Russians in Los Angeles. Sociological Monographs. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press. | |

Slepniak, a.k.a. Sergei Mikhailovich Kravchinskii |

||

| 1888 | The Russian Peasantry. New York: Harper and Brothers. | |

Story, Sidney Rochelle |

||

| 1960 | Spiritual Christians

in Mexico: Profile of a Russian Village.

Ph.D. Dissertation (Anthropology), University of California, Los Angeles. |

|

Struve, Nikita |

||

| 1967 | Christians in Contemporary Russia. Translated by L. Sheppard and A. Manson. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. | |

Tolstoy, Leo |

||

| 1933 | Polnoe sobranie

sochinenii. Volume 27, pp. 351-354 (May 2,

1900). Полное собрание сочинений : Complete Collection of Works online page 210 shows 2 requests from Molokans in the Caucasus for Tolstoy's help to go to America — 1 March 1900 from Kars province, and 2 May 1900 from Erivan governate. When he got the second request, Tolstoy wrote: "I thought I was finished dealing with molokans, ..." which may indicate he was annoyed with them. There is no indication that he responded to them after these dates. A request for copies of these messages, if they exist, has been forwarded to Tolstoy archives in Russia. |

|

Wilson, Bryan R. |

||

| 1970 | Religious Sects. A Sociological Study, London: Oxford University Press. | |

Young, Pauline V. |

||

| 1927 | Family Organization

of the Prygun |

|

| 1928 | Occupational Attitudes and Values of Russian Lumber Workers. Sociology and Social Research 12(6): 543-553. | |

| 1932 | The Pilgrims of Russian Town: The Community of Spiritual Christian Jumpers in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. | |