Dukh-i-zhizniki in America

An update of Molokans in America (Berokoff, 1969). IN-PROGRESS

Enhanced and edited

by Andrei Conovaloff, since 2013. Send comments to

Administrator @ Molokane. org

< Chapter 6

Contents Chapter 8 >

Chapter 7 The Second World War

Contents

- College Boys Go To Russia Updated: 27 June 2017

- World War II Begins, 1939

- Draft Panic

- Petition the Government

Again

- Trip to Washington and Report

- Russian Relief

- New Cemetery on Slauson Avenue Updated: 28 March 2020

- War Economy

- 90% Joined the Military

- Avoid Jail, Go to CO

Camp

- Deadbeat Faith,

Unpaid Debt : $17,024

- Turkey, Kars, Mount Ararat

- Korean War (1950-1953)

Added: 18 December 2016, Updated 31 October 2020

- "Asian" Flu Pandemic

(1957-1958) Added: 24 March 2020

- Vietnam War and Later Updated: 18 December 2016

After 1928, most of persistent members of Spiritual Christian congregations in Southern California (including Fresno County) were gradually being transformed to Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations. It was a confusing process that took more than 25 years, causing many to abandon their heritage faiths as the zealous chastised those whom they believed to be unfit.

1. College Boys Go To Russia

In the Summer of 1939, four college graduates, most from the University of California at Los Angeles (U.C.L.A.), planned to take a grand educational trip across the U.S., the Atlantic, Europe and into Russia to see the world and visit the homeland of their parents. They were all American-born. 3 Pryguny (John A. "Coe" Shubin, Alex "Al Serg)" Serguiff, ___ ) and 1 Russian Jewish fellow, together bought a car to which they attached storage trunks for camping gear and baggage. A used encyclopedia provided maps and was their guidebook. Each contributed $200. To pay for his part, Serguiff auctioned his car, which really advertised their trip in "The Flat(s)." He sold 200 tickets at $1 each. Several congregations invited the boys to send-off prayers and donated money for them to deliver to home villages and families in Kars, Turkey (formerly Russia). "We were treated as if we were going to the moon," reminisced Dr. Shubin, an economist, 50 years later.

Shubin organized the trip as a continuation of his education, which he could not have done alone. They visited not only the major tourist attractions (Grand Canyon, Yosemite, etc,) but many major factories (General Motors, Alcoa Aluminum, etc.), and studied each state in the encyclopedia as they passed through to review geography, history, economy, etc., firsthand. On the East Coast they got jobs on a freighter in exchange for shipping their car to London. In Europe they had their car and more cash. Taking the car, Shubin and Serguiff separated from the other 2 to find relatives near Kars, Turkey. Serguiff stayed near Kars and illegally took photos, while Shubin took the car to Odessa and drove though Russia back to Europe. Both Shubin and Serguiff got stuck as the war was escalating. To earn money to get home, for most of 1940, Seguiff taught physical education at the American University west of Istanbul, and Shubin drove the car as a taxi in Paris. Each came home separately. The Prygun, I cannot recall, was killed in Washington riding a bicycle to work.

"Coe" was my uncle, my mother's brother. "Al Serge" was my wife's 1st cousin, once removed (her mother's 1st cousin). In 1992, when I met my wife's grandfather in Russia, and mentioned that I knew Aleksei Serguieff, he reminised about his nephew's visit to Kars in 1939 as if it was last week.

The boys daring trip inspired several Maksimisty in Los Angeles to also travel cross-country to ask the Turkish Embassy in Washington D.C. for visas so their congregations could return home to Kars oblast, near Mount Ararat. They were denied visas which undoubtedly spiritually disturbed many who believed their salvation would only occur if they joined with Maksim Rudomyotkin on Mount Ararat during his resurrection to be saved before or during the Apocalypse.

2. World War II Begins, 1939

PAGE 109 The outbreak of the war in Europe on September 3, 1939 did not at first excite the elder Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokan people because it seemed that the country would remain aloof from the conflict. Immediately upon the commencement of hostilities in Europe, the government of United States declared its neutrality. There were many powerful political leaders and groups in the nation who were vociferously insisting that the United States must not become involved in that war under any circumstances (non-interventionism). The President himself assured the American mothers that their sons would not he sent overseas to fight a war.

Furthermore, after Germany conquered Poland in September, 1939, the world was lulled by the so-called Phony war of the winter 1939-1940 into a belief that the war will terminate soon and without much further bloodshed. So the American public, including the elder Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans, remained unconcerned.

But this was quickly changed from complacency to frenzy in May

1940, when Germany in a quick thrust attacked France, Belgium,

Holland and Denmark and, after defeating these nations and

driving the English army that came to the aid of France out of

France, began preparations for invading England.

It was then that the government of the United States began its

frenzied preparations for possible confrontation with Hitler.

Among other measures of preparation, Congress passed the Selective

Training and Service Act of 1940 in September, of

1940, a Universal Selective Service law, providing

for the first

peacetime compulsory military service for all men

between the ages 18-45.

But while the law was being debated by Congress, the elder Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan concern

was expressed by groups of appointed individuals in weekly

conferences called for that purpose.

There were no meetings or conferences with, or representation by, Molokane in Northern California, who are considered a different faith, infidels to these Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths.

All

Dukh-i-zhiznik youth attended school, were integrated, many

assimilated, many were patriotic and wanted to get in on

the action to stop Hitler, and see the world. Youth met in

three separate organizations.

- Since 1926 at the U.M.C.A., rear

(alley) of 122 S Utah Street, open for all Spiritual

Christian youth, but avoided by the most zealous faiths.

- Since 1938, at the "House of Light" mission, 1127 S. Mott St (Karakala neighborhood), where a club was formed which evolved into the Y.R.C.A. Also avoided by the most zealous faiths.

- The most zealous only met at Zagreb

(Zagrab) sobranie for youth meetings, molodoi

sobranie ("Young Church"). The location was in

the alley between Utah and Clarence streets, a few

doors north of the U.M.C.A.

PAGE 110 The

discussions at these meetings clearly showed that the question

of religious objection to military service was neglected by the

brotherhood during the past 20 years or since the end of the

first World War. No serious effort was made during that time to

indoctrinate the younger generation in that phase of our

religion on the assumption, perhaps, that the last great war was

the final one and on the further assumption that in the unlikely

event of a war occurring, our boys will he automatically exempt

from military service, for the conviction was still unanimous

that the United States constitution forbade the induction of

religious objectors into the armed services against their will,

and, since the Spiritual

Christians from Russia Molokans were

recognized by the United States government in 1917 as historic

objectors to military service*,

they would therefore he exempt automatically.**

* Spiritual Christian immigrant men from Russia were excepted from military during WWI because they were not citizens and did not speak English. No congregations were officially recognized by the U.S. government as "Peace Churches."

** Dukh-i-zhizniki had no school system to teach pacifism. Zealots rejected the U.M.C.A. and Y.R.C.A. as forbidden "clubs" which did not indoctrinate youth with their Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths. Rather than approaching the clubs managed by non-zealots, the zealots formed their own youth training school, which continues today as "Young Church".

4. Petition the Government Again

During the course of these conferences every one looked for

guidance to Ivan G. Samarin, the much respected elder and the

sole surviving veteran of previous negotiations with government

officials and other Spiritual Christian

faiths, particularly the Dukhobortsy. Mr.

Samarin reminded the conferees that in 1917 when the brotherhood

decided to petition President Wilson for exemption from the law,

it at the same time filed a proclamation (Addenda I) with the county

clerk's office advising whom it may concern that the Dukh-i-zhizniki

Molokans of

America were objecting to military service on religious grounds.

This proclamation, he said, was

published in legal publications of the county and recorded by

the County Clerk in the county Hall of Records but, because of

the pressure of time at the time of signing, only 259 heads of

families were able to sign the document, therefore, without consulting an attorney Mr.

Samarin was of the opinion that the signatures of all heads of Dukh-i-zhiznik

Molokan

families should now add their names a similar document. For this

purpose he urged that each congregation register the names of

its members in membership books which would then be proof to the

authorities of authenticity of a person's claim to exemption

from the draft PAGE 111 on the same basis as

their fathers in 1917. As the actual terms of the proposed new

law were not yet known, every one was still in the dark

concerning the actual requirements to he demanded from the

objectors, however, several congregations did as he suggested while zealots refused

because they feared written lists and other things "not

spiritual" a man gave the advice, not the Holy Spirit.

Simultaneously with these discussions the local Society of Friends (Quakers) were also concerned about the proposed law and were likewise holding periodic meetings in their meeting houses in Whittier and Pasadena which were addressed by visiting Friends from the east who were in close touch with the congressmen in charge of framing the law.

An invitation from the Friends in Whittier to the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans to attend their meeting was gladly accepted by several younger, English speaking Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans. Those who attended these meetings learned that according to the terms of the proposed law, a registration in congregation church membership books will be far from adequate proof of the genuineness of a person's claim to a conscientious objector status, consequently, Mr. Samarin's suggestions were mostly disregarded.

But when the Selective Service and training act Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 became an actual law, the Act in its entirety was published in all the local newspapers and its terms became available to all who cared to study them. Of course everyone did, including the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans, therefore it was then unanimously decided by all congregations that a more serious approach to the question should be attempted.

It was further decided to do as the fathers did in 1917,

namely to address a petition to President Roosevelt asking him

to exempt the Dukh-i-zhizniki

Molokans

from compulsory military service in like manner as they did President Wilson did

in 1917.

For this task the brotherhood again turned to Ivan G. Samarin, begging him to compose the petition as he did so many times before. Without hesitation and in spite of his advanced age (he was 83), he did not refuse and wrote two PAGE 112 petitions; in one of them [Oct. 15, 1940, Addenda IV] he incorporated his contention that the government should he reminded that there are now many more Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans people than the 259 families who signed the proclamation in 1917. The other, addressed to President Roosevelt [October of 1940] requested exemption from military service for all Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan young men.

Having prepared the petitions, the previous custom* was followed and three delegates were

chosen to present them in person to the authorities in

Washington as was done by the brotherhood in 1917.

* Berokoff probably used the word "custom" (ritual) instead of the more accurate "protocol" to imply that they always (customarily) send delegates to petition the Tsar in Russia (President in USA) as Molokane did in Russia in 1805, because he falsely thinks he is Molokan and personal contact with the nation's leader is their customary ritual.

It was seen, however, that most suitable men fell into the

category of middle aged individuals who were not fluent in the

English language. It was then decided that the wisest and most

practical method of election was to submit four names from the

older men from whom the brotherhood would select two as

delegates and also two names from the younger, English speaking

men from whom one was to he elected to go as the delegation's

interpreter.

But this was easier said than done because all Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths and factions had to he satisfied since all were participating in the deliberations. But although all were participating, not all were willing to abide by the results of the balloting. Some believed that that would be a departure from Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan traditions while others feared that the results would he a foregone conclusion in favor of the "Big Church" because of its large membership, therefore, these abstained from voting although they were present at ballot time. "Big Church" had the largest membership, who on the average were more diverse, integrated and assimilated, educated and liberal; and, most members supported the U.M.C.A. and Y.R.C.A.

The results of the balloting showed that David P. Meloserdoff

(presviter) and Walter P.

Shinen (publisher) were elected as

the religious delegates and

William J. Pavloff (businessman, singer)

as interpreter but because Pavloff was absent from the city at

the time of departure to Washington, John K. Berokoff, who

received one vote less than Pavloff, automatically took the

former's place as, the delegation's interpreter.

5. Trip to Washington

and Report

PAGE 113 The

delegation was instructed to contact the local officials of the

Selective Service before departure for Washington in the hope

that the same results could be obtained locally, namely: that by

showing them the letter of Gen. Crowder had

written to Shubin, Samarin and Pivovaroff in 1917 (Addenda III),

exemption from military service could be secured locally but the

local officials in the person of a Lt. Black replied that they

had no authority to grant a blanket exemption to anyone and

suggested that National Headquarters should be contacted,

therefore, the delegation departed for Washington on the night

of sudnyi den' Sudni

Dien (судный день : holiday : day

of atonement), on October 9, 1940, returning on

October 19 with a written report (below)

signed by all three members.

On the evening of one of the last days of Kushcha Kusha* Feast of

Tabernacles Holiday a capacity crowd gathered in

the Big Church to hear the report. The report, included

herewith, explains the results of the trip better than anything

that could he written now, therefore, it would he superfluous to

add to it at this time.

* Kusha (куша) is the typical diaspora Dukh-i-zhiznik mis-transliteration and slurring of Куща (kushcha), their holiday. Kusha is a colloquialism for "a large sum of money."

| THE REPORT

Beloved brothers and sisters! Being selected by you for such a vital mission and through your prayers, we completed our trip. We now have the honor to submit to you the results of your trust. At the time of our departure we set before ourselves the problems of your charge. We decided that our primary purpose was to present the petitions to the three branches of the government, but also to discuss with the head of Selective Service and to get an explanation from him to those questions which the officials of the Selective Service in Los Angeles, Lt. Black, was unable to explain. In the first place we

applied to the Post Office, General Delivery and

received three letters of recommendation from a friend

of Mr. Shinen to three congressmen and one to PAGE 114

Chairman Edward J. Flynn

of the Democratic Party of America. We presented one

of these letters to Congressman Ford who, in turn

wrote us a letter of introduction to Lt. Col. Lewis B. Hershey,

the head of Selective Service. We then went to the office of Congressman Charles Kramer (1933-1943) who was not in his office at the time. He was an unsuccessful candidate for the Democratic nomination for mayor or Los Angeles in 1941. Having in our possession a good letter of introduction from Congressman Ford to that particular office which most concerned our mission, we decided to go there immediately. Thomas F. Ford served on the Los Angeles City Council for 2 years (1931-1932), and as a Democrat in the U.S. Congress (1933-1945). In the afternoon of our first day in Washington we went to the office of Lt. Col. Hershey who received us pleasantly and courteously. Presenting our petition to him, we asked him to explain that part of the law which the officials in Los Angeles were unable to explain, namely, how will those be dealt with whose conscience forbids them to participate in war activities? To this we received the following explanation: By Presidential order each Local Board was sent the following instructions: Every case that might cause a misunderstanding or doubt in the minds of the Board concerning the induction or the exemption from the draft of a registrant, must he decided in favor of the registrant. He explained further that when the Local Board will be examining the questionnaire that will be completed by every registrant whose turn will come up by the lottery, it must first look into all possible causes for exemption before examining the question of conscientious objection. For example; if a registrant is married or has dependent children, mother, father etc. or if a registrant is an alien or is employed in a vital government job, he is to he exempted on those grounds; but if no such grounds exist then the question of conscientious objection is to he dealt with. He remarked that this is done to forestall any possible grumbling in the nation against conscientious objectors. To our question: Nevertheless, how will those he dealt with who will be found to be religious objectors, he replied; "The PAGE 115 law says that they are to be placed in work of National Importance but what is "work of National Importance" has not yet been determined and that Congress has not yet allotted money for that purpose." He then told us that concerning this matter he is conducting talks with representatives of the Quakers and Mennonites and that he suggested to them that they establish a central committee of all the so-called Peace Churches so that he would not have to deal with 10 or more different representatives but with only one. He suggested further that we confer with Paul French, the Quaker representative. Following this conference with Hershey we immediately took a train to Philadelphia to talk with French, for we were told that he was there at that time. Arriving at their headquarters in Philadelphia we discovered that he was not there but we were received by another, Ray Newton with whom we conferred for about 1-1/2 hours. He revealed to us their plan that they were about to propose to the government and asked us for permission to take a copy of our petition to the President to which we assented with pleasure. He told us that Paul French is more familiar with that proposal than he was and gave us the address in Washington where we could find French in the morning. We returned to Washington the same night and in the morning we met this man. After our conference with him we asked his advise on how best to present our petition to the President. Following his advice we set

out to the Executive Office of the White House where

we presented our petition to the President's

secretary, General

Watson. We were advised that for some time past

the President was not receiving petitions personally

from anyone but that our petition would reach him

quicker if it is presented to him through his

secretary. At this time we gave them the letter of

recommendation that we had PAGE

116 to Chairman

Flynn in which was a statement that these People (the

Spiritual Christian Dukh-i-zhizniki

From there we went directly to the War Department and appeared in the office of the Secretary of War. After reading our petition to the Secretary, they affixed their stamp to it and returned it to us saying that we must take it to the Selective Service office of Lt. Col. Hershey. After this we decided to await the arrival in Washington of Dr. Clarence A. Dykstra from Los Angeles, the newly appointed head of Selective Service whom, we were told, we could see on Friday, October 18. Returning to the hotel we there met the Mennonite representative, Henry Fast, who informed us that they are working on the conscientious objector matter closely together with the Quakers. That same evening we received a telephone call from the White House informing us that our petition has been acted upon and that it was forwarded to the Selective Service where it properly belonged, the caller further told us that all our negotiations on that matter should he conducted with that office. In reply to our inquiry as to when Dr. Dykstra will succeed Col. Hershey, we were told that Col. Hershey will remain as Dykstra's assistant and that all such matters will he handled by Col. Hershey. We then decided that on the

following day, October 16, we will present the third

petition the copy of the petition to the President

to Col. Hershey and after receiving a reply from him

we will return home.

In the meantime [October 15, 1940] we

received by airmail a letter of recommendation from Dr. Pauline

V. Young to a friend of hers, a Justin

Miller* who was a

justice in the United States Appellate Court. In the

morning we went to the office of this judge but he PAGE 117

could not receive us personally. Instead, he informed

us by letter that being a member of a Court which

might he called on to decide cases involving

conscientious objectors, he could not compromise his

position by receiving us personally but that in his

opinion he could he of more valuable service to

conscientious objectors in the event such cases should

reach his Court for a hearing.

From there we again proceeded to Hershey's office and, presenting our third petition to him, we requested a reply in writing which he courteously agreed to give us. He also gave us a sample of a special questionnaire for conscientious objectors which the latter will be required to complete. He also agreed to write to all the Local Boards in Los Angeles concerning our petitions. After this we decided to return home. Concerning everything above set forth, we submit the following summary

|

The delegation returned to Los Angeles in the middle of the Kushcha (Куща)

On the evening following the delegation's return a large crowd assembled in the "Big Church", tensely expectant to hear the desired word that all was well and that no mother was to worry about her sons being enrolled in the armed forces.

The reading of the report, together with the comments of the delegates and explanations of Hershey's letter and of the special form, (form 47) DD Form 47 (discontinued 1985): Department of Defense, "Record of Induction," declaration of conscientious objection was a disappointment to many who were steadfast (postoyannie)* in the belief that the rulers in Washington knew all about the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans and that they were quite cognizant of the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans' exemption from military service in 1917. But the majority of the younger and the middle aged people were not so sanguine and received the report with proper understanding of the circumstances.

* "Steadfast" is translated here into Russian (postoyannie) to show the reader how that word is used by Dukh-i-zhizniki in context when describing their faith movement. When Dukh-i-zhizniki describe Molokane, postoyannie is an insult; but, when Dukh-i-zhizniki describe themselves, postoyannie here probably means "convicted' or "convinced," a positive attribute.PAGE 119 The people of this age group, who were either born in the United States or were young enough to attend school here knew that it was fantastic to assume that any group could receive such blanket exemption. There was no edict or decree in the U.S.A., like the ukaz in Imperial Russia. They knew, but not all the elders born in Russia knew, that the affairs of the nation are regulated not by men but by the constitution and the laws made in accordance with that document, which meant that all laws were applicable equally to everybody. They knew also that no one in authority, not even the President, had the power to grant special concessions or exemptions to any individual or any group and that Congress itself could not pass such a law because it would raise such a storm in the country that it would jeopardize the position of all conscientious objectors in the country and, in any case, be quickly declared unconstitutional.

But even this younger age group was unable to grasp immediately the complicated process of classification and of the various appeals and investigations incidental to the process. In point of fact it was more than a year after this that the whole procedure of appearance before the Local Boards, the Appeal Agent, the Cold War investigations by the FBI, and the appearance before the Hearing officer and, at times, an appeal to the Presidential Appeal Board, was mastered, and then only by the advisors appointed for the purpose.

These representatives Dukh-i-zhizniki in America apparently acted on their own, not consulting draft attorneys, nor joining in conversation with any of the organizing peace churches Mennonite Central Committee, Brethren churches, or Society of Friends.

Meanwhile, as Hershey told the delegation, no one knew what the Work of National Importance Under Civilian Direction was to be. The Local Boards bided their time pending instructions from Washington but at the same time discouraging potential C.O.s by misrepresenting facts of the proposed program being prepared for them by telling the potential C.O. that he personally would have to support himself while in camp etc., etc. So things quieted down for a while. The only action taken by the brotherhood at this time was to appoint an advisory council to help the registrants with their problems.

PAGE 120 This body so appointed functioned for the duration of the war and for about ten years thereafter. (It functions to this day under a different set-up.) It was named originally "The Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan Advisory Council for Conscientious Objectors" but later shortened to "The Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan Advisory Council."

The previous title used in WWI Russian Sectarians Spiritual Christian Jumpers was correct without the word "Molokan." But the youth were afraid and ashamed to be uniformly known as "Jumpers", "sectarians", or having to explain the meaning of the Russian label Prygun which not all supported. They were of different faiths. Perhaps they thought their chances of acceptance by the government was better if they lied saying they were "Milk-Drinkers" rather than "Holy Jumpers." During WWI the Sionisty, Novyi izrail', Pryguny, Maksimisty, etc. primarily called themselves Spiritual Christian Jumpers in English.

On December 17, 1940 the secretary of this advisory council received the following letter from Paul French, the executive secretary of the recently formed "National Service Board for Religious Objectors" (NSBRO)

| Washington, D.C. December 13, 1940 Dear Mr. Berokoff: Cordially Yours, |

The Advisory Council, which was then composed of Nick Eropkin, chairman; Peter F. Shubin, vice chairman; John W. Samaduroff, treasurer; W. J. Pavloff and John K. Berokoff, secretaries, having no authority to commit the brotherhood to such collaboration, sought more detailed information before submitting French's proposal to a mass meeting, therefore, on December 20, 1940, the secretary wrote him as follows:

Without wasting any time, Paul French wrote back the following on Dec. 26, 1940:

Upon receipt of this letter, the Dukh-i-zhiznik Advisory Council, recalling Hershey's statement to the delegation that he did not like the idea of dealing with each Peace Church individually but preferred that all of them form one organization to represent them all before the government, decided to submit the matter to a mass meeting of the brotherhood for a decision.

The following week a mass meeting attended by about 500 persons openly discussed French's proposal. It was explained by the Dukh-i-zhiznik Advisory Council that without a doubt many problems will he faced by the community as a whole as well as by its individuals in the following months, perhaps years, requiring representation in Washington but that inasmuch as the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans will be unable to maintain their own regular representative* there, the National Service Board will he able to represent them instead.

* If Dukh-i-zhizniki were unanimously committed to being a "Peace Church" they would have been able "to maintain their own regular representative." Instead they chose the cheaper alternative offered.After a full discussion, the proposal was accepted unanimously and a sum (amount omitted) was collected as an initial contribution to PAGE 122 the National Service Board. The contribution was forwarded to the National Service Board and henceforth the name Dukh-i-zhiznik "Molokan Advisory Council" was included in the letterhead of that organization.

At the same time the meeting was informed that in answer to the Council's inquiry concerning Work of National Importance, Mr. French replied on December 2, 1940, that the question is still in the discussion stage, that there was nothing definite as yet about the program.

But it seemed quite certain that the Quakers, Mennonites and the Brethren are agreed to operate and pay for the maintenance of camps to which their conscientious objectors will he assigned to work in National Parks, in Soil Conservation and Forestry Division for which they will receive no pay. Other conscientious objectors must pay their own costs.

It seemed likewise certain that, although these three church groups will accept assignees from any other church body, they will expect each church group to defray the costs of maintaining their members as far as possible, therefore, if the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans are to he assigned to such camps, they must he prepared to carry their share of the load.

This proposition was accepted also. It was further agreed that every family in the brotherhood was to contribute one dollar per month for the support of any and all Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans assignees to these camps, the sum to be administered by the Advisory Council. A large sum was enthusiastically collected on the spot at the same time receiving the blessing of the Holy Spirit through the prophets

However, this spirit of cooperation continued for only a brief period. It should he noted that, although the mass meeting filled to capacity the largest of the community meeting houses the Big Church the number of people actually was relatively a small portion of the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokan community. The most zealous opponents of the Big Church were probably absent. The majority were indifferent, believing that somehow, someone PAGE 123 else will see to the welfare of their sons.* The slow pace of the draft program, especially the slow pace of the program of Work of National Importance, added greatly to this general apathy.

* A communal society would view all children as common property, a common burden to be supported by all the members irrespective who the parents are, or are not, including childless couples and unmarried adults. Berokoff's oral history indicates that these various Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths were no longer communal, if ever actually communal, nor totally dedicated to pacifism, especially if it cost money.The nation was starting the program of training of recruits entirely from scratch. Camp grounds had first to he acquired and located, barracks had to he built, personnel for training the recruits had first to he trained, etc.

On a smaller scale but no less complicated was the preparations for the conscientious objectors. It will he recalled that Hershey told the Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan delegation that congress failed to provide funds for the operation of the conscientious objector program, consequently the Selective Service System was compelled to finance it from a special fund at the disposal of the President. For this reason the assignment of C.O.'s to work of National Importance, or Civilian Public Service camps as they were henceforth to he known, was delayed for ten months following the first registration, during which time the government was refurbishing the old, abandoned C.C.C. Civilian Conservation Corps camps scattered throughout the various mountain ranges of the country. Consequently, the first Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans did not report for work to the C.P.S. camp until June 23, 1941 although

This delay was fortunate for the individual concerned for it eventually shortened his stay in camp by six months but it led the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokan community to believe that their Advisory Council was being deceived, that there will never he any such program for the C.O. and eventually all their boys will be drafted into the armed forces. This belief was strengthened because many boys, unknown to their parents were already accepting the draft, indeed, were volunteering for the service. The number who enlisted was 10 times more than their C.O.s in camps and jails. For this reason the enthusiasm shown previously for the C.O. program was gradually being eroded. The parents of those who were already in the service saw no further need to contribute to a fund from which they would not benefit personally. (Since 1980, similar charity bias is expressed by some Dukh-i-zhizniki who will not donate or verbally support the Heritage Club Scholarship Fund, unless members of their family are recipients.)

PAGE 124 Up to the time of the Pearl Harbor incident about 250 Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans filed claims of objection to military service. About two-thirds (170?) of these were married, therefore exempt from the draft. Part of the balance (80?) entered the armed forces as non-combatants. Of the rest, three were in the C.P.S. camps and the remaining were in the various stages of processing their claims. Perhaps twice as many refused to claim a C.O. status and were either inducted or were volunteers in the armed forces.

At the same time, and especially after the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the attitude of the local draft boards became extremely antagonistic towards all C.O.'s. By placing all sorts of obstacles in the way of the registrant's claim for a C.O. classification, they compelled each one to appeal to the state Appeal Boards which meant that the registrant had to submit to an investigation by the Department of Justice through the agency of the F.B.I. who thoroughly checked the claimant's school and police records, questioned his school teachers, his employers and neighbors, his friends and enemies, his relatives and his church elders and, if his record disclosed a minutest infraction of Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan rules, he would he denied the proper classification, thus forcing him to make the difficult appeal to the Presidential Appeal Board, or failing there as it sometimes happened, to submit to arrest and to a trial in the Federal Courts. These procedures further complicated matters for the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokan community as it was probably meant to do. As a matter of fact it caused some grumbling among the members because the complicated processes delayed considerably the time such claimants were ordered to report to camp, meanwhile his presence at home incited unfavorable curiosity and suspicion in the minds of his neighbors.

As a rule members of the various Local Boards were entirely unfamiliar with the Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans and their religion. Although they all knew of a large colony of immigrants from Russia

* Revealing the Dukh-i-zhiznik faith to a non-believer is apostasy, against an order from Rudomyotkin. By falsely claiming to be Molokane, the Dukh-i-zhizniki were able to hide their actual faiths. However in 1915 in Arizona, the Maksimist prayer book was translated into English and given to Americans to introduce their faith to their new neighbors. Berokoff reprinted the Arizona 1915 English prayer book in 1944 and was bullied for doing so. Though Young's Pilgrims of Russian Town (1932) was published with adequate descriptions of the Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths, copies of this book was evidently not submitted to the draft boards.In March of 1941 Harold Stone Hull Hall, secretary of the local branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Pasadena, asked for a statement on Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan history to which a three-page reply [Addenda VIa] was sent reciting briefly the Dukh-i-zhiznik Molokan background, its history, reasons for emigrating to the United States and their present attitude to war. Mr. Hull replied on April 11, 1941 thanking the Council for the material and adding;

"I very much appreciate your fine letter of April 4 in which you send the excellent statement on the Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths Molokanism. Paul Comly French of Washington, D.C. again asked us to send it to him, so we are getting it off by air mail. I hope that he will be able to put the material to good use in Washington so that people in Selective Service headquarters will understand more of the position of your faith." (See Addenda pp. VI-D, VI-E and VI-F.) [These Roman numbers are wrong, which further indicates that the Addenda were rearranged and edited in haste probably just before press time.]Meanwhile, facilities for Work of National importance were made ready to receive the C.O.s and the draft boards began slowly to assign them to the various camps throughout the country. One camp was opened in the San Gabriel mountains, near the town of Glendora, California, to be operated by the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers).

According to a rule laid down by the National Headquarters of the Selective Service, a registrant could not he assigned to any camp located less than 150 miles from his home, consequently, only those Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans living either in Arizona, Oregon or in the San Joaquin Valley were eligible for assignment to PAGE 126 the Glendora camp. Residents of Los Angeles and vicinity had to he satisfied with camps farther north.

MAP

The data shows that the typical Spiritual Christian C.O. was in more than 2 camps, on the average, during his Alternative Service work, and, 2 men were in 4 camps. About 70% changed camps at least once.

Soon other camps were opened; one in Cascade Locks, Oregon (C.P.S. 21, no name); one near Coleville (C.P.S. 37, Antelope) and another near Placerville, California (C.P.S. 37, Placerville).

On June 23, 1941 the first Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans assigned to the C.P.S. arrived in the Glendora camp (C.P.S. 2, Jan 1942 became #76) . Two months later another two arrived in Cascade Locks. By April 30th, 1942, six more were working near Placerville. By June 30, 1942 there were a total of 14. Gradually the number grew until eventually the total assignments reached a top figure of 88* in various C.P.S. camps in California and other places.

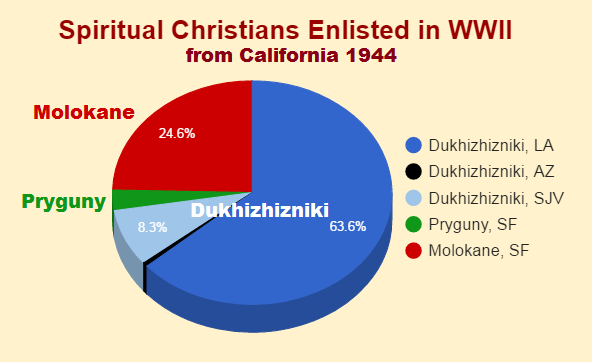

* Only 78 Spiritual Christians are listed in The Directory of Civilian Public Service, May 1941 to March 1947 (1947), 3 of which are Dukhoborsty, one is Molokan, and none were Pryguny. The official count at the end of the war was 74 from Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths.Chart of the 5 top camps populated with Spiritual Christian (SC) C.O.s doing Alternative Service during WWII.

| Camp | Official Name | Nearest Town | State | Workers | SC | % Workers | % Total SC | Cumulative % |

| 2 / 76 | Glendora / none | San Dimas / Glendora | CA | 757 | 50 | 6.6% | 31.8% | 31.8% |

| 107 | none | Three Rivers, Camp Buckeye | CA | 404 | 41 | 10.1% | 26.1% | 58.0% |

| 37 | Antelope | Coleville | CA | 513 | 19 | 3.7% | 12.1% | 70.1% |

| 31 | Placerville | Placerville, Camino | CA | 592 | 16 | 2.7% | 10.2% | 80.3% |

| 35 | none | North Fork | CA | 474 | 13 | 2.7% | 8.3% | 88.5% |

The data show that nearly 90% (88.5%) of Dukh-i-zhizniki with 1 Molokan and 1 Independent Doukhobor, worked at 5 (one-fourth) of the 20 C.P.S. camps populated by Spiritual Christians in California during WWII.

It was common for men to transfer between camps, assigned where needed. Many of the Dukh-i-zhiznik transfers were to voluntarily join other Dukh-i-zhizniki who congregated among 5 camps. Half of the men were at 2 camps closest to Los Angeles Glendora (2/76) and Camp Buckeye (107, near Three Rivers), and oral history in many families falsely implies that "everybody" was 1 or 2 camps.

While these fortunate ones were being assigned to the camps, other Dukh-i-zhizniki

The majority of Spiritual Christian

6. Russian Relief

Following the invasion of Russia by Hitler's army in June of 1941, many persons devoted their energies to the collection of funds among the Spiritual Christians

The participation of the brotherhood in this work was not unanimous. Many individuals did not take part in it and one Los Angeles congregation as a whole (the Old Romanoffskaia), a part of the Arizona and a part of the Kerman communities refrained from this activity, basing their stand on the prophesy of Maksimist Afonasy Bezayeff in 1921, which forbade participation in PAGE 127 Russian relief during the great famine there. Nevertheless, in April 1943 it was announced by the group working in the relief and that over $16,000.00 was collected for that purpose.

7. New Cemetery on Slauson Avenue. Also see: Chapter 2 : Funerals

| A funeral procession approaching First

Street from N. Gless Street. Third from left in front

row is Afonasy T. Bezayeff and next to him holding

handkerchief to face is Philip M. Shubin. 1909. Click to Enlarge |

About this time also late in 1941* a 17 acre site for a new cemetery was purchased on East Slauson Avenue, as the old one on Eastern Avenue was filled to its utter capacity. A non-profit corporation was organized to hold title to the land and to operate the cemetery as the "Russian Molokan Christian Spiritual Jumpers Cemetery Association, Inc."*

* Registration: September 23, 1941 ; State ID: C0188838. Issued 8 days after the first burial of F.K. Kashirsky..

MAP

https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll4/id/13359/rec/1

At that time the property was in an incorporated Los Angeles County area called "San Antonio Rural," named after the original Spanish land grant Rancho San Antonio. After 1960, this area became the City of Commerce, with mail delivery from the Bell post office.

Oral history told by Luba Prohoroff, in Arizona on March 18, 2021. She is the widow of Wm Wm Prohoroff III ("Billy Pro"). In the 1930s, her father-in-law, Bill's father Wm Wm II, was a delivery driver for A&W Root Beer in the Los Angeles area. In the late 1930s he knew people were looking for a cemetery larger than what they had on 2nd street. As he was driving along Slauson Ave, he saw a strawberry farm for sale, and gave the information to David Miloserdoff, presviter of "Big Church" which in 1933 moved their building from the Flats to Lorena street. Miloserdoff supported buying the farm, which was purchased, but LA County would not issue a land use permit for a cemetery. Luba said that a "Kashirsky" was the first buried, and then they got the cemetery permit.

Miloserdoff was the last most dynamic influential leader of the Brotherhood of Spiritual Christians in America. He united and socially crossed over into nearly every social division, and led caravans from Los Angeles to visit Dukhobortsy in Canada.. My father told me that Miloserdoff tried to make friends with everyone. If a bunch of young guys were drinking beer, he would join them and drink some beer. If Maksimisty were jumping, he would join them in jumping. The "Molokan Review" annual picnic magazine was also launched in 1939, during this time of movement eastward from the Flats.

I only find "Miloserdoff" mentioned in J.K. Berokoff's book 3 times, only in the Addenda. Berokoff "cancelled" Miloserdoff from the body text of his history. If Miloserdoff had not co-authored and signed 3 letters, he would not have been mentioned in Berokoff's history book.

Genealogist Nancy Poppin-Umland collected a photo of the Kashirsky grave marker (right) taken along the chain link fence. The caption says: "Fatsay (Frank) Kire'vich (Kerry) KASHIRSKY (about 1844 - September 15, 1941) Died in Kern County, CA. and is the first man to be buried in the 'New Molokan Cemetery' on Slauson Ave., in Commerce, CA."

Two more were buried in 1941 D.P. Hropov, and S.F. Bagdanoff. At least 30 people were buried in 1942. See "Burials per year ... " below.

The Kashirsky head stone appears to be identical to grave markers in Guadalupe Valley, Mexico homemade concrete with circle impressions using machine gears (sun shapes), and a recessed inscription area hand scratched. He probably moved to Kern County from Mexico.

Apparently zealot families who refused to attend the U.M.C.A. (1926+), "Big Church" (1933+), and the Y.R.C.A. (1939+), also refused to be buried in the "new cemetery" (1941+) with "unclean" people, and had to buy additional cemetery land from the Serbian United Benevolent Society, 4355 2nd St, Los Angeles, CA 90004-5101. Though the Orthodox Serbians were gracious Christians who aided the non-Orthodox Pryguny in 1910 with their first cemetery land in America, then shared additional land with Dukh-i-zhizniki after 1941, in the 2000s the zealous Dukh-i-zhiniki refused to allow the Serbians to annex 2nd street to be used for parking which they could share. Was this because the Serbians were "unclean" and "Orthodox"? Or did the Holy Spirit order these Dukh-i-zhizniki to not cooperate? Some other reason? In any case, why did they buy land from them to bury their most Holy people facing East at the cross on top of the Serbian Orthodox Church, then refuse to cooperate?

A workable set of by-laws were adopted by which every christened Spiritual Christian Molokan was eligible to all the privileges of membership in the Cemetery Association by a payment of $5.00 per person, young or old. The full sum was soon collected by these means and the $15,000.00 was paid off. ($15,000/$5 = 3,000 people.)

Though originally incorporated for all descendants of Spiritual Christians from Russia, in the 1980s this cemetery became dominated by Dukh-i-zhizniki who took control after director Alex Tolmas died in 2006. A census analysis has not been done, nor is wanted, for fear of revealing the facts. In the 1980s, new rules and an organizational structure (komitet) was codified specifying that burials, ceremonies and management was limited to only those of the Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths, members of select congregations. Now that Dukh-i-zhizniki are in control, they want a komitet. But the 3 Maksimist congregations and their Dukh-i-zhiznik descendants who opposed the "Big Church" komitet in 1933 will only accept burial in the Old Cemetery, which is registered but never had a komitet it remained Spiritually clean in their minds, though an Orthodox priest sanctified the ground, which was purchased from an Orthodox church, and is adjacent to an Orthodox cemetery.

A plan was adopted whereby, among other provisions, no mounds were to he permitted over the graves as customary in Russia but the grounds were to remain level permitting the planting and maintenance of a grass lawn, similar to other cemeteries in America. In addition, the grave markers were to be of maximum uniform size on which the inscriptions were to conform to specific Old Russian Molokan form and style.

The late cemetery director, Alex Tolmas often commented that there never was a rule for uniformity, only maximum dimensions so they can mow the grass. And, said Thomas, "Everyone buys a gravestone to the maximum size, thinking that is the rule, which it is not. They all copy each other." See: By-Laws, Article XII, Monuments and Inscriptions, 1. Monument Size. Thomas explained that he much preferred the minimum size, a flat ground plaque, because they are much cheaper and much easier to work around than standing stones.

But these provisions were too radical for some members of the brotherhood, Maksimisty who did not want to be spiritually tarnished by unclean people (pork-eaters, non-believers, ... ) in the same cemetery, which may be a remnant rooted in their old Russian Orthodox belief to not be buried with those of other faiths. It was asserted by this faction of Dukh-i-zhiznik-Maksimisty that elimination of the mounds was a further departure from the ways of the forefathers, that the earth of any given grave was not to he hauled away to another location but should remain on that particular grave, consequently, these formed another group to purchase a small plot of ground adjacent to the old cemetery on Eastern Avenue at its western end. Thus there are two cemeteries serving the brotherhood that is otherwise of the same faith. Actually they are diverse Dukh-i-zhiznik faiths, fractionated by burial beliefs, congregation indoctrination, and willingness to hold a non-religious, temporal, secular, business meeting (komitet).

Many of those who protested against the Slauson Avenue Cemetery soon conformed to it. They broke with tradition by not preparing the body at home, paying a mortician, buying caskets and allowing embalming, which discards most of the blood, which they do not know occurs. Many believe the body must remain intact and not placticized with embalming fluid.for the resurrection.

The chart shows the approximate count of burial dates on grave markers totaled by year. By 2011, about 2670 people had been buried at the Slauson Ave. cemetery. Notice that the red trend line from 1942 to 1974 rises and should have passed 100 per year by 2000, but abruptly falls to a steady rate of about 40 per year from 1975 to the present. I heard a reasonable explanation for this rate shift from Alex Shubin in the 1980s. Several times I heard him say that he gets invited to a lot of funerals, and recently "about half of them are for burials at Rose Hills" (Memorial Park and Mortuary), in Whittier. I knew a few of these people, and to me, this indicates that non-observant descendants of Dukh-i-zhizniki in Southern California, especially the more prosperous, have self-selected their exit from their heritage tribes by choosing to be buried among the "Americans," and at a "nicer" cemetery in the landscaped hills. It appears to be their final statement for assimilation, and avoidance of hosting a huge meal, standing for hours, bowing to the floor, praying for their dead relatives (which most indoctrinated by American Protestantism do not believe in), kissing people they don't know, and having to do it a year later for a memorial (pomenki) ritual. Some buried in Rose Hills or from the Slauson Ave. chapel will host a catered meal at a restaurant or a large house to partially fulfill that part of the ritual and socialize with relatives, as many "Americans" do.

Outlined in yellow, the image above, modified from Bing maps March 2021, shows the Spiritual Christian cemetery property on Slauson Ave, City of Commerce. The original 17 acres has been reduced to about 14 acres due to widening of Slauson Ave. and construction of the Santa Ana Freeway. The cemetery uses about 8 acres, and the remaining 6 acres are rented to Premier Trailer Leasing. Burials began in 1941 in the section marked "1" and continued today in section 4. Section 5 will be in the lower left. An adjacent Jewish cemetery shows graves placed much closer together, and how the Jews created income by selling half of their property to a company. In 1998 real estate investors offered to buy part of the property for $435,000 an acre, were rejected, and appealed to the youth via the press. ("Laid to Rest Among Their Ancestors," Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1998.)

At least one burial with no grave marker was a disfigured soldier mislabeled as "Petrushkin" by the military and delivered to his widow, Betty Nazaroff-Petrushkin, who told me her tragic story about 1980. At the mortuary, Betty realized that several of the body features did not match her husband, especially the wedding ring on the man's finger. Because a funeral was in progress, people were invited from Kerman, and food bought, the mortician was afraid to upset his lucrative customer base and unethically advised Betty to pretend everything was on schedule. He said that we can always dig up and change the caskets later, when elders are not looking. In emotional trauma, Betty decided to not do anything more after the funeral. She soon learned where her husband was actually buried, and returned the wedding ring to the widow of the soldier still in the Slauson Ave cemetery with no grave marker. The experience changed Betty's life. She enrolled in an embalming program at Cerritos College, and got a funeral directors license. For many years she was the only Russian-speaking embalmer and funeral director in the State of California, and perhaps on the west coast. Based on what she learned about how the funeral industry has corrupted her Russian heritage, she recommended that an embalming room be installed at the cemetery, to return preparation of the body from businesses back to the community. The dead would be treated with respect, and the family would save huge costs, especially if the cemetery could construct caskets.

Cemetery director-manager Alex A. Thomas (1921-2006) told me in the 1980s that he was for Betty's proposal, and that he wanted to learn how to do embalming himself. The board voted against it, including making caskets, which would have greatly reduced the cost of burials to maybe $1000 plus the cost of the plot. Another proposal was to construct a meeting hall on the property specifically for funerals. When community contractors and builders were consulted, many from the Heritage Club, it was decided to avoid building permits and install "temporary" buildings (trailers on wheels). A chapel was made from 2 full length trailers, and toilets were in a separate trailer. This was an attempt to address 2 problems: (1) reducing the cost of funerals by eliminating hearse rental to and from meeting halls; and, (2) providing minimal traditional funerals for marginal members, who rarely attend Sunday meetings, families assimilated (married out), etc..

The board consists of one representative from most Dukh-i-zhiznik congregations, except maybe 2 or 3 of the most zealous congregations (probably including "Blue Top" and "Clark Street") who maintained the Old Cemetery as their final resting place.

Even though a congregation, on the average, may not be zealous, it takes only one zealous member to absolutely object to anything. Due to these few zealots, the enormous effort and expense of conducting a full traditional funeral, and the fact that many of the marginal members were dying, who rarely attend and whose families have more often married "out", even belonging to a different faith. a funeral was pressed to find a way to hold short funerals at the cemetery, specifically for marginal, non-practicing Dukh-i-zhizniki those unworthy of a full traditional 2-day funeral, burial and feast. Occasionally a highly honored Dukh-i-zhiznik would get a 3-day funeral at one of the more zealous congregations. After much study, it was decided to use 3 portable buildings, 2 combined for a "chapel" and 1 for toilets, which did not require expensive buildings and permits. Using the chapel eliminated renting a hearse to and from the congregation meeting halls. A few have learned that a hearse is not "required", any vehicle is allowed, as long as the burial permit is correct, which anyone can get.

Funerals now cost about $13,000 for the mortuary, plot and head stone, plus $2,000 optional for a large feast about $15,000. In the early 2000s, Martin Orloff, presviter of Dom Maleetvee, was shocked to learn about the exorbitantly high cost of special-order caskets, and arranged to have them built by a local cabinet maker much cheaper, and he bought a stockpile of "funeral clothes" for those who need them. Still the total cost remains way over $10,000. A few people have chosen a no frills cremation for under $1000.

On 2nd Street, the new section of the old cemetery today has no mounds, and in stark contrast to the old-old cemetery next to it, has cut green grass and uniform headstones, some flat on the ground. In the 1980s, the old cemetery remained traditionally untended, covered with weeds and hand-made grave markers. The grave markers were remarkably different, some using broken ceramic tiles, hand-made with concrete, stone and wood. The Americanized younger generation was embarrassed by their old-world antiquity and tore out most all the original grave markers to replace them with modern Western ones an act of assimilation. Very little remains of the traditional old-Russian style which was the basis for the division of cemeteries, except the fact that they are geographically separate, symbolizing the division of most Maksimist-Dukh-i-zhizniki from the rest. Some suspect that the more zealous congregations prefer this "exclusive" cemetery because E. G. Klubnikin was buried there.

Also see Chapter 2 : Funerals. The congregations that owned their own cemetery and dug and covered their own graves, like Arizona and Mexico, retained the dirt mound, which traditionally fell when the casket decomposed within a year. Modern American graves use a concrete shell which prevents the dirt collapse, which was adapted in Arizona about the 1980s.

In the 2000s, the Clark Ave (Podval sobranie, Klubnikin, Shubin, Clarence Street, 605, Clarky) congregation, was shunned by the Los Angeles congregations so they created their own small cemetery. Andre and Kathrine Hozen rezoned their small farm in the mountains of Riverside county, west of Temecula to allow for a 0.29 acre (4200 sq. ft, about 50' x 200') cemetery called the "Molokan Sanctuary." It is managed by trustees Andre Hozen and William Kachirsky. After 6 members were buried it became a legal cemetery in 2011 for up to 250 graves. In March 2021, Andrei Hozen died and was buried in his own cemetery.

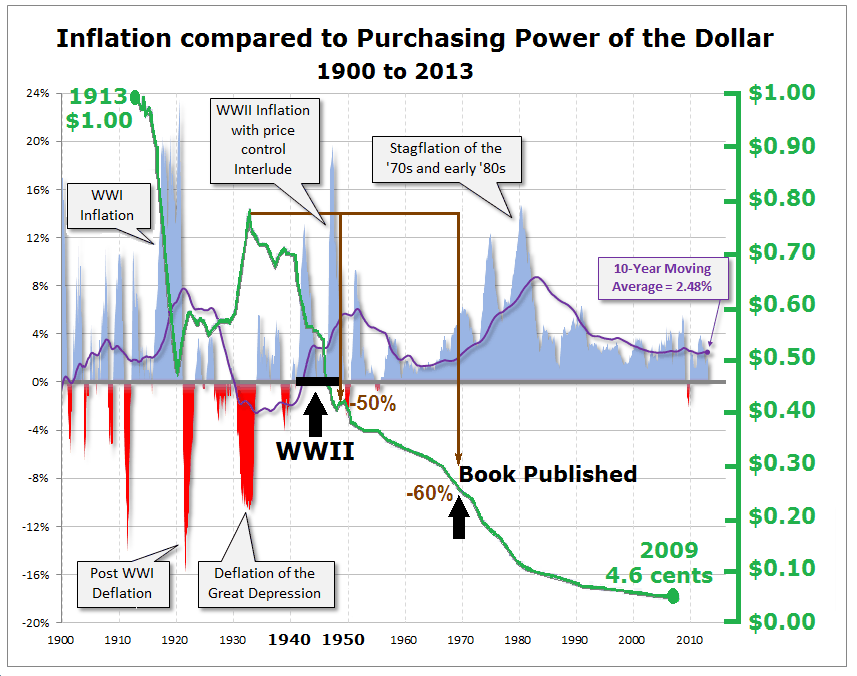

8. War Economy

In other respects the life of the brotherhood proceeded in

routine fashion. The following is an excerpt from a contemporary

diary (secret author): "Even as in

the days of Noah, so shall the coming of the Son of Man be." (Matthew

24:37) These words could well apply to us at the

present time. The Dukh-i-zhizniki Molokans are

disturbed PAGE 128

individually as each family loses a son to the armed forces,

but, collectively there is little change. Weddings and other

doings* in meeting

halls churches every Sunday. Every

one is working and making money ... Money is plentiful although

prices on everything are skyrocketing.**

Sugar will he rationed***

next month beginning 27 April 1942.

It is planned to issue one pound per person per week. But for

the time being there is enough of everything for all weddings,

baptisms, funerals etc., in spite of threatened "rationing***."

(At the annual U.M.C.A. picnic of 1943, 750 lbs. of meat were was prepared and consumed. At this time also, $300.00

were

was

collected for the Russian war relief.)